One hundred and fifty years ago, my great-great-great-grandfather, Oliver Winchester, founded the Winchester Repeating Arms Company in New Haven, Connecticut. His pride and joy was the revolutionary Winchester repeating rifle, one of the first guns to fire rounds repeatedly, taking away the cumbersome need to stop and reload. The Winchester became an icon of the American frontier – used by cowboys, Native Americans, outlaws, sheriffs and even President Theodore Roosevelt. As the settlers went steadily westwards after the civil war, the Winchester was their weapon of choice – it became known as the Gun that Won the West, celebrated in celluloid numerous times by a gun-toting John Wayne and the youthful Jimmy Stewart.

Used by the Turks in their 19th-century battles against the Russians, and by the Mexicans in their uprising against the French-backed emperor, the Winchester became known around the world. The company’s officials were always wary of having a history of their beloved rifles written – we don’t want dead buffalo and Indians on every page, observed my great-great-uncle Ed Pugsley, the chief engineer.

My introduction to the Winchester came on a hot August afternoon in 1987, more than a century after Oliver Winchester had started manufacturing his rifles. Visiting my American relatives in Connecticut, we fired tennis balls from an adapted elephant gun into the sparkling waters of the Long Island Sound, just for the fun of it. My great-aunts, legend has it, would fire the tennis-balls at intruders who ventured too close to their family compound.

We were having a high old time at the family compound in Branford, Connecticut, which had been built by Oliver’s daughter Jennie and her husband, Thomas Gray Bennett. As a distant family member from London, I had a dim idea of what the Winchester repeating rifle was, having watched a healthy dose of westerns on TV during my early 70s childhood. And as a former air cadet in east London, I learned to fire a .22 rifle and a .303 – but always on a shooting range, in a highly restricted environment. And here were my relatives merrily shooting tennis balls into the blue yonder, with guns inside their summer houses – it was an introduction to the gun culture of America, so very different from that back home in Britain.

My grandmother Molly, who inherited a not-inconsiderable sum of money as the great-granddaughter of Oliver, married an Englishman and left her family in New England for Cambridge, England. She was ambivalent about the legacy of the Winchester, and would occasionally grunt disapprovingly about gun money, shaking her head. As a child, she took me to CND rallies in Cambridge, and we watched deeply alarming videos about Hiroshima. A strange juxtaposition, the gun heiress turned fervent supporter of nuclear disarmament.

That visit to my American clan stayed with me as I went off to university. I began to read all I could about Oliver Winchester and his rifles. He was born a penniless farm boy, trained as a carpenter building flying buttresses in churches, successfully patented a bestselling shirt collar, and then decided to invest his considerable cash in guns just as the US civil war was looming. When my husband and I moved with our sons across the Atlantic in 2004, my interest in all matters Winchester increased. We bought the caretaker’s cottage on the family’s summer estate of Johnson’s Point in Connecticut, and the idea of writing a book about these mysterious descendants of yesteryear evolved.

As I was learning about my Winchester heritage, I was reporting for the BBC on the phenomenon of mass shootings in America. In the aftermath of the Sandy Hook elementary school massacre in 2012, when a gunman killed 20 young children, six adults, his mother and himself, I arrived to witness a scene of unbearable agony. In this picture-perfect Connecticut town, not far from where Winchester built his repeating rifles, Christmas trees had been put up in memory of every dead child. I stood outside the temporary mortuary where the bodies of the murdered six- and seven-year-olds lay, and wept, imagining how I would feel if my own six-year-old was inside.

At school, my children learned what they called “huddle drills” – what to do if someone is having a really bad day, as my then seven-year-old son explained brightly. I told him reassuringly that I didn’t feel that he would ever have to do a huddle drill for real. In the wake of Sandy Hook, Congress failed to pass even modest gun-control legislation, such as ensuring background checks on people who buy weapons at gun shows.

As the descendant of a dynasty created by manufacturing weapons of war, writing a book has forced me to examine my own feelings on the topic. One of our relatives, Sarah Winchester, was supposedly so racked with guilt and haunted by the spirits of those killed by the Winchester that she started building a house in California because a medium advised her that endless building would appease the dead. Construction only stopped when she died. Thousands flock every year to the bizarre Winchester Mystery House, pulled in by the irresistible tale of guns and guilt. There is scant truth to the myth – but that’s another story.

I am fascinated by the Winchester legacy, but I don’t feel responsible for or guilty about the past. I see our family as a thread in the tapestry of America’s history. There is no airbrushing over the brutality of the settling of America’s west, in which guns were central. The Winchester was deployed to kill Native Americans defending their historic lands – and yet they also used the rifle with devastating effect, most notably at General Custer’s last stand. African Americans also embraced the Winchester as a defensive weapon in the bloody period after the civil war, in which lynching was common. “A Winchester rifle should have a place of honour in every black home,” as the civil rights crusader Ida B Wells wrote in 1892. And so the Winchester was used for many different causes during a violent period.

As a soon-to-be dual US and British citizen, it is hard not to be struck by the starkly different approaches to gun control. When I was growing up in Britain, strict gun laws were passed in the aftermath of the Hungerford massacre in 1987 and then additional legislation was passed after the Dunblane school killings. In the US, where the second amendment provides a constitutional right to keep and bear arms, the debate is very different. Although opinion polls suggest the public supports controls on the sale of assault weapons and background checks for everyone who buys a gun, the National Rifle Association has so far lobbied successfully against these measures.

Hillary Clinton is running in favour of what she calls commonsense gun control, while Donald Trump is staunchly against her proposals. Why such different approaches in two countries sharing a common language and heritage? Guns were embedded in the culture of America at the time of its violent revolutionary war against England, and used to expand the territory of the new nation.

When the question of gun control in the US came up in the 1970s, the surviving Winchester relatives were staunchly opposed. But then they had never been fans of Uncle Sam having a say in their business. In the 1890s, when men at the Winchester factory were regularly blown up as they mixed the explosive primer used in the ammunition, my great-great-grandfather, Thomas Gray Bennett, perfected a system where the men mixed the primer using mirrors to keep themselves at a safe distance. He was most pleased to have kept meddling factory inspectors at bay through his own ingenuity.

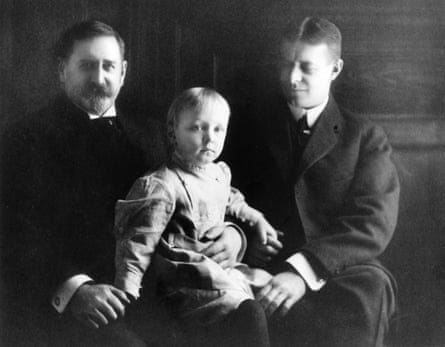

In fact, it was heavy-handed government-administered contracts that led to the end of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company as a family concern. When the first world war loomed into view, my great-grandfather, Winchester Bennett, was at the company helm. A highly strung man, he had suffered from nervous anxiety for much of his adult life and was nursed throughout by his devoted wife, Susan. Winchester, named after the gun, was not equipped to deal with the rigours of wartime production and had to leave the company just as the factory was gearing up to produce millions of rounds of ammunition and tens of thousands of rifles for the allied wartime effort. Bennett was later treated for addiction at a Connecticut facility specialising in patients with psychiatric disorders.

His father, Thomas Gray Bennett, though he was nearly 80, came back on to the company board at this time of personal and professional crisis. Thomas Bennett never approved of doing business with the US government, which insisted on fixed-price contracts. As the costs of labour and materials skyrocketed because of wartime demand, Winchester made less and less money. By the time the war ended, the company was millions of dollars in debt. A wild plan to diversify into selling products “as good as the gun” followed, and the company used the excess factory space left over from the war to manufacture ice-skates, penknives, fishing rods, washing machines, cutlery and all manner of household items. The scheme was a monumental failure and the Winchester Repeating Arms Company went into receivership in 1931.

A special summer home is the legacy of the company for our generation. As I rake the beach for oyster shells, if I narrow my eyes I can conjure up the image of a cowboy out west galloping on his horse, his trusty Winchester at his side. The great-aunts have passed on now, but I can still hear the echo of their laughter as they fire the tennis-ball gun out into Long Island Sound.

Winchester: Legend of the West by Laura Trevelyan is published by IB Tauris, £20. To order a copy go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min. p&p of £1.99.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion