Amy Hempel Is the Master of the Minimalist Short Story

Amy Hempel’s best short stories reveal how rich spareness can be.

Amy Hempel’s introduction to writing fiction was a workshop in her late 20s with Gordon Lish at Columbia University. Lish had recently left his post as the fiction editor of Esquire to become an editor at Knopf in 1977. There he continued to publish many of the writers whose careers he had launched at the magazine: Raymond Carver, Barry Hannah, and others. For his students’ first assignment, he instructed them to write about their worst secret: the thing they had done that, as he put it, “dismantles your own sense of yourself.” “Everybody knew instantly what that thing, for them, was,” Hempel recalled in an interview with The Paris Review almost 30 years later, after three spare collections of short stories—Reasons to Live (1985), At the Gates of the Animal Kingdom (1990), and Tumble Home (1997)—had established her as a star among Lish’s protégés. She continued: “We found out immediately that the stakes were very high, that we were expected to say something no one else had said, and to divulge much harder truths than we had ever told or ever thought to tell.”

The result, for Hempel, was “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson Is Buried,” which appeared in TriQuarterly in 1983. A narrator, who may or may not be Hempel, is visiting her dying best friend in the hospital. When I first read it, I was awed by the specificity with which the story—fewer than 3,000 words, many of them dialogue—conveys both the intimacy and the mundanity of the encounter: the trivia the two women discuss; their macabre jokes (“The end o’ the line,” says the patient, draping the cord of her bedside phone around her neck); their conversations with doctors and nurses; the memories they share. I was surprised to learn that for Hempel, the story was about failing her best friend, which was the “worst secret” she uncovered in Lish’s class. The story turns on the narrator’s refusal to spend the night in the hospital with her friend, a moment described so obliquely that one might miss it. But the story is also much larger—a chronicle of grief, and a testimony to the universal helplessness of the living in the face of death.

One or two or three human beings navigating a situation of exquisite emotional intensity, sketched with the fewest possible words—this has become Hempel’s signature. “You leave out all the right things,” another writer once told her. Everything nonessential is chipped away, from dialogue markers to physical descriptions, allowing the reader to home in on the dismantled self. In the early story “Pool Night,” a single line suffices to convey a teenage boy’s powers of attraction: “I knew girls who saved his chewed gum.” (That boy will later perform a stunt he calls the “Fire Dive,” sprinkling his clothes with gasoline and lighting them on fire before diving into the pool.) The writer Rick Moody, in his introduction to The Collected Stories of Amy Hempel (2006), admires “her nearly Japanese compaction.” In her attention to word choice and the rhythm of her lines, she is sometimes closer to a poet than a prose writer—two of her stories consist of a single sentence. Here’s “Housewife,” from Tumble Home: “She would always sleep with her husband and with another man in the course of the same day, and then the rest of the day, for whatever was left to her of that day, she would exploit by incanting, ‘French film, French film.’ ”

Though Hempel’s style places her squarely in the camp of Carver and others who popularized minimalism, she doesn’t embrace the term. “It came to denote what certain reviewers felt was missing in fiction—conventional plot or obvious emotion, for example,” she told The Paris Review. “Some of these critics had a very limited sense of what a story could be.” Indeed, many discussions of minimalism overlook that it’s as much a matter of subject as of style. In contrast to a writer like Deborah Eisenberg, who has produced a similarly spare number of stories but whose field of vision is more broadly geopolitical, the work of Hempel’s cohort is domestic and interior—Carver’s couples sitting around a table talking about love. Hempel’s domesticity, however, isn’t as stable as the word implies. Like her previous collections, her latest is a book of renters and house sitters; people on a temporary leave from their lives that threatens to become permanent, their ennui insufficient to spur them to action.

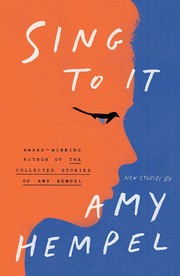

For Hempel, a story often takes place not at the moment of crisis but in its aftermath—a housekeeper, for instance, trying to clean up the stain a dying woman left on a rug (“When It’s Human Instead of When It’s Dog”). A story is a father and children taking a pleasant road trip during which the threat of something ominous never plays out (“Today Will Be a Quiet Day”). A story is a woman who knits her way through a profound loss (“Beg, Sl Tog, Inc, Cont, Rep”). Even Hempel’s novella-length pieces—“Tumble Home,” from 1997, and “Cloudland,” in Sing to It, a new collection after more than a decade of silence—are juxtaposed snippets of scenes and images rather than sustained narrative.

The word minimalism no longer feels pejorative. To the contrary, the form has recently resurged in the work of writers such as Rachel Cusk and Jenny Offill, both of whom, like Hempel, construct bare-bones fictions on the scaffolding of their lives, using narrators who share some of their characteristics. Especially for a woman writer, it’s a way to write autobiographically without appearing self-indulgent. (“The whole book is true,” Hempel told The New York Times Book Review when Reasons to Live came out.) The style leaves little room for mistakes, and several stories in Sing to It misfire or simply fail to coalesce. They’re snapshots rather than collages, vignettes rather than dreamscapes. But when the approach works, turning the pages is like swimming in a lake and suddenly finding the bottom drop out beneath you, leaving you to get your bearings amid unanticipated depths.

Hempel’s background in journalism—she started out as a medical reporter—taught her the value of grabbing a reader from the start, of writing “a sentence that would make someone want to read the next one.” The opener to “I Stay With Syd,” in Sing to It, is an instant classic: “I wasn’t the only friend Syd’s married man hit on the time he came to see her at the beach.” The narrator is jaded, flippant: She goes home to “attend to the business end of a sleeping pill.” But—as will become a theme of the volume—this survivor is also a damaged soul. The bumper sticker on one character’s car reads, i brake just like a little girl.

“The Chicane,” another highlight of Sing to It, begins: “When the film with the French actor opened in the valley, I went to the second showing of the night.” A convoluted backstory is packed into the next seven pages. More than 30 years ago, the actor had an affair with the narrator’s Aunt Lauryn, then a college student, which resulted in an unplanned pregnancy. (He remained “in character,” the narrator says wryly, and didn’t acknowledge it.) Lauryn had a miscarriage and attempted suicide by overdose. Later, she married a Portuguese race-car driver and returned with him to the States, where they had a son, James. But she became dissatisfied, and on a trip back to Lisbon, she overdosed again. Some years later, the race-car driver told the narrator that the Portuguese police taped the phone call Lauryn made as she lay dying (evidently a routine practice with international calls from Lisbon).

She wanted to talk to her mother, and hear her mother tell her from thousands of miles away that James was sleeping in the guest room in his crib, and that it was hard to make out what she was saying—could she speak up?—and that she would feel better when she woke up in the morning, and then ask her mother to stay on the line while she sang herself to sleep.

A chicane is a trick, as well as a series of sharp turns on a racecourse, and another trick/turn awaits before the story ends. But the poignancy of that conversation between mother and daughter—not even a scene, just a summary—is what lingers. We don’t need to resolve the questions: why Lauryn wanted to spend her last minutes on Earth on the phone with her mother, or why the race-car driver chose to share the existence of the tape with his dead wife’s niece, or what drove Lauryn to suicide. (“When life is easy, it’s an easy thing to take a life,” a character in another story in this collection says, prompting the narrator to wonder whether the same isn’t also true when life is hard: “Sometimes the answer is yes when a person asks if it would kill you to get the mail.”) As in all her best stories, Hempel plants a small bomb with a surprisingly powerful detonation.

When other stories in this volume fail to yield the same richness, it’s because the connections that should feel organic are instead forced or just unfulfilled. “The Second Seating” has another perfect opener—“The three of us were taken with the vodka fizz made with elderflower and basil so we stayed on and had the raw kale salad and heirloom tomatoes with medallions of halloumi”—but doesn’t rise above its subject matter: a group honoring the memory of a dead friend by eating at a restaurant he had wanted to try. “The Doll Tornado,” inspired by a piece of installation art in North Carolina, strains to draw a link to the civil-rights movement.

“A Full-Service Shelter” is a polemic against animal cruelty rendered in the form of a chronicle of volunteers at an animal shelter. It’s almost saved by the musicality of its lines—nearly every sentence begins with “They knew me” or “They knew us”—but finally strikes the same note too many times. (In the acknowledgments, Hempel thanks “my fellow members of Compassion Care … work[ing] to save the lives of dogs in extremis.”) I found myself recalling Lish’s instructions to his fiction students: There is no secret shame here, no hard truth.

Both seem in ample supply in the collection’s closing novella, “Cloudland,” which returns to one of Hempel’s perennial themes: disconnections between mothers and daughters. The narrator is a woman who, in her youth, gave up her child at birth in a home for unwed mothers. Now middle-aged and working as a home health aide in Florida, she has spent her life adrift, anchored only by her occasional fantasies about being with the daughter she might have had—selling Girl Scout cookies or accompanying her on a road trip (“I keep the seat belt buckled over the empty seat”). She eventually learns from a book that unwanted babies born in that home were starved to death and buried under the apple trees in the backyard. In its best moments, as we watch the narrator painfully piece together the fragments of her life, this story is reminiscent of “Tumble Home,” the moving novella in which Hempel grappled with her mother’s suicide. Some passages and images, though, feel spliced in from elsewhere. I found myself wondering whether “Cloudland” was an attempt to marry elements of her own story with something unrelated to it (in the acknowledgments, she thanks Chuck Palahniuk for pointing her to a book about a maternity home in Nova Scotia).

Hempel’s method of transmuting life into fiction is nothing if not exacting. “I leave a lot out when I tell the truth. The same when I write a story,” she once wrote. Choosing what to let in, and how to deploy it, is even more important. “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson Is Buried” doesn’t gain anything from the knowledge that it is based on Hempel’s secret shame. That knowledge might even detract: It’s when fiction doesn’t quite stand by itself that the reader, distracted, wanders in search of biographical clues. “I live in so many sentences,” Hempel has said. The best of those—riveting in their precision—also take on new lives of their own.

This article appears in the April 2019 print edition with the headline “The Art of Leaving Things Out.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.