A Conversation With Randall Munroe, the Creator of XKCD

Q: What would happen if a beloved web comic created a series of ... physics explainers?

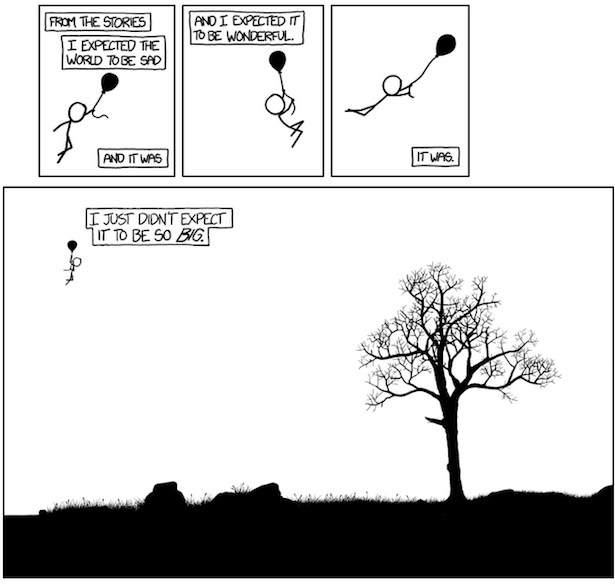

Randall Munroe began his career in physics working with robots at NASA's Langley Research Center. He is famous, however, for engineering a creation of different kind: the iconic web comic that is xkcd. Last week, Munroe won the web's wonder for approximately the thousandth time when he published comic #1110, "Click and Drag," a soaring, spanning, surprising work that encouraged users to explore a fanciful world through their computer screens.

As Rev Dan Catt pointed out, if you printed the comic at 300dpi, the resulting image would be about 46 feet wide.

But Munroe, work-wise, is no longer dedicated exclusively to xkcd. He recently launched "What If?," a collection of infographic essays that answers questions about physics. Published each Tuesday, the feature -- a blog extension of the xkcd site -- aims to analyze the kind of wonderful and fanciful hypotheticals that might arise when the nerdily inclined get together in bars: "What would happen if the Moon went away?" "How much wood would a woodchuck chuck ...?" Some of What If's recently explored questions include: "What if everyone actually had only one soul mate, a random person somewhere in the world?" and "If you went outside and lay down on your back with your mouth open, how long would you have to wait until a bird pooped in it?" and -- the most recent entry -- "If every person on Earth aimed a laser pointer at the Moon at the same time, would it change color?"

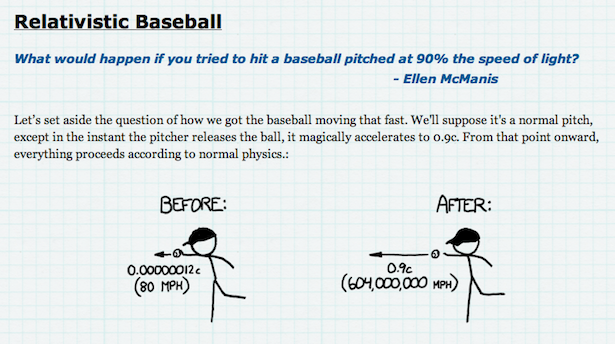

I recently spoke with Munroe about What If, xkcd, creativity, baseballs pitched at 90 percent of the speed of light ... and how, for him, The Lord of the Rings helped lead to it all. The conversation below is lightly edited and condensed.

First things first: Why did you create What If?

It actually started with a class. MIT has a weekend program where volunteers can teach classes to groups of high school students on any subject you want. I had a friend who was doing it, and it sounded really cool -- so I signed up to teach a class about energy, which I always thought was interesting, but which is a slippery idea to define. I was really getting into the nuts and bolts of what energy is, and it was a lot of fun -- but when I started to get into the normal lecture part of the class, it felt kind of dry, and I could tell the kids weren't super into it. And then we got to a part where I brought up an example -- I think it was Yoda in Star Wars. And they got really excited about that. And then they started throwing out more questions about different movies -- like, "When the Eye of Sauron exploded at the end of The Lord of the Rings, and knocked people over from this far away, can we tell how big a blast that was?" They got really excited about that -- and I had a lot more fun doing it than I did just teaching the regular material.

So I spent the second half of the class just solving problems like that in front of them. And then I was like, "That was really fun. I want to keep doing it."

So What If was basically a spin-off of the class?

That was where the idea came from. I actually wrote the first couple entries quite some time ago, based on questions students asked me in that class -- and then on another couple questions that my friends had asked. It was only recently that I finally managed to get around to starting it up as a blog.

The variety of the topics you tackle is incredibly broad. How do you figure out the best way to explain all these different, complicated subjects to people?

Part of what I'm doing is selectively looking for questions that I already know something interesting about. Or I've stumbled across a paper recently that was really cool, and now I'll keep an eye out for a question that will let me bring it up -- something I can use as a springboard. So in a conversation, someone might say, "Money doesn't grow on trees." Okay, well, what if money did grow on trees? Our economy would collapse. On the other hand, we would switch to a new currency. It's complicated.

What I like doing is finding the places in those questions where normal people -- or, people who have less spare time than I do -- think, "This is stupid," and stop. I think the really cool and compelling thing about math and physics is that it opens up entry to all these hypotheticals -- or at least, it gives you the language to talk about them. But at the same time, if a scenario is completely disconnected from reality, it's not all that interesting. So I like the questions that come back around to something in real life.

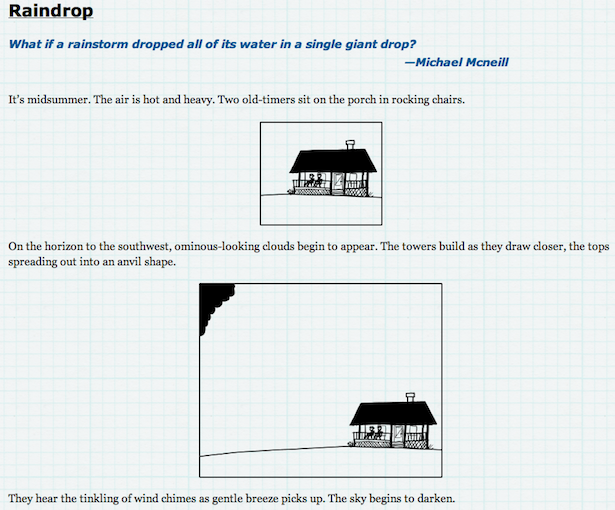

And the great thing with this is that once someone asks me something good, I can't not figure out the answer, you know? I get really serious, and I'll drop whatever I'm doing and work on that. One of the questions I recently answered was, "What if, when it rains, the rain came down in one drop?" And I was like, "Well, how big would that drop be?" I know a little bit about meteorology, and then, before I knew it, I had spent four hours working out the answer.

Why that need to answer? Is it because people are asking you -- because you want to help them out by answering the questions for them?

Oh, no, no, no, there's nothing altruistic about it! It's just like, once it gets in my brain, it keeps bugging me, and I don't know the answer, but I'm really curious. What really happens is: I have an idea for what the answer is, but then I want to figure out if I'm right or not. So I have to keep working to find out. And oftentimes, in the process of learning I'm wrong, I'll run into something even cooler. And then once I find that, I just want to tell everyone about it.

So I basically set up this blog to flatter all of my random impulses. And it's been a lot of fun so far.

And how do you decide which questions you ultimately commit to answering?

For the first few entires I wrote, I just wanted to make sure this format made sense. So I wrote a couple entries with questions just from my friends. And then when we put up the blog, we included an "Ask a Question" link. And since then, the volume of questions has been high enough that I don't think any set of two or three people could read them all. So I pretty much just sit down whenever I have a few spare hours and go through them and answer the questions that come in and try to see if there's anything that would make a good article.

Of the ones you've done, do you have a favorite so far?

The one that I recently put up: "What would happen if the land masses of the world were rotated 90 degrees?" I'm kind of a geography and map geek, so I started drawing out the maps for that, and I think that ended up being, by a large margin, my longest entry. And I kept on thinking, "Oh, what about this thing?" and "Oh, I should really go back and read more about trade winds and figure this out." So I had a lot of fun with that.

But I also really enjoyed the first one that I posted, and that's been one of a lot of people's favorites: the one about the baseball thrown at 90 percent of the speed of light.

That one I have a soft spot for because it was the first one I put up. And I heard from people who know a lot more about these things than I do -- I got email from a bunch of physicists at MIT saying, "Hey, I saw your relativist baseball scenario, and I simulated it out on our machine, and I've got some corrections for you." And I thought that was just the coolest thing. It showed there were some effects that I hadn't even thought about. I'm probably going to do a follow-up at some point using all the material they sent me.

I imagine, given all that, that the posts are incredibly labor-intensive. How long would an average one take you?

I'm still deciding how long to make them -- and part of that is just figuring out how long it takes to answer the average question. When I started out, I didn't really know what to expect from the questions, so I wasn't sure if I'd be able to answer them quickly or what. But I think, now, it's about a day of work in which I don't do much else.

That's it? I was figuring it'd take much longer!

Well, that's a day of solid work -- I mean, most people don't actually work through a whole day. I certainly don't. So in practice, it's a few days, because there's a lot of email checking, or having to go run an errand.

Makes sense. And, design-wise, I love how each article stands on its own -- a single product on a single page. Since that's the same structure you use for xkcd, I'm wondering: Why did you choose to repeat that format?

Especially because I was so delayed in actually getting the site up, I had a lot of time to think about how I wanted it to look. Did I want to have individual entries, or did I want to do more of a blog format, or did I want to have a bunch of questions answered as they came in? So we settled on the current format, and it seems to work pretty well.

One of the things I've learned with doing xkcd is that you sort of give people, "Here's the thing, and here's the button you can press to get another thing." Sometimes that can be more easy to digest than "here's a long page of things." You can read through it, and you get to the end and think, "Wow, I just read a whole bunch. Do I really want another page like this?"

I'm not a huge fan of some of the infinite scrolling things that are happening now. I think it's really annoying to want to read partway through, and then you navigate away, and can't get back.

xkcd led to sales of posters, books, and other items. Does What If, at this point, have a business model?

When I first started xkcd, it was all stuff I drew during classes -- because I wasn't paying attention to the lecture. And then when I started drawing them from home, I found that I'd have a lot of trouble coming up with ideas. And then I'd get a project and start working on that -- and I found that, instead of it taking up more of my time, I had more comic ideas per day and was drawing more of them. So they all reinforced each other.

The format would definitely make sense as a book. But for the moment, it's just been so much fun to write and answer. My experience of the Internet has been that if you make something really cool, the neatness speaks for itself. And that's much more important than trying to make something marketable -- trying to make something into a product. So I just found that if I'm steadily trying to make cool things and putting them up, some of them, in some way or another, have a business opportunity.

Is there a direct relationship between xkcd and What If? Do they inspire each other?

Mostly, I just think it's helped me because it's given me all this cool stuff to read through. I'll sometimes be researching a question and then be like, "I don't think I can turn that into a thing." But I did find this paper while I was doing it, which led me to this other paper, which led me to this blog, which led me to this comic.

And it probably made me annoying! I read this book once about this guy, A.J. Jacobs, who read the entire Encyclopedia Britannica and wrote about the experience. He said he had the problem where someone would be like, "Pass the salt," and he'd be like, "Oh, did you know that salt was originally used in medicine for this kind of thing, and then we learned it causes this?" And people would be like, "Just pass the salt."

I had something similar. When I was doing the money chart, someone would say, "Oh, I can't afford to move into a new apartment," and I'd say, "Oh, I know, a lot of people are in that situation because the income has changed like this, whereas the rents in this state have shifted more than in other states, because blahblahblahblahblah -- all these economics."

It was like, "Okay, wait. Pull back. This is not interesting."

I learned very early on in life that not everyone wants to hear every fact in the world, even if you want to tell them everything you've ever read. Which is why it's probably good that I have the comic schedule that I do -- because I would figure out something to say every 30 minutes if I were forced to by my schedule. But it would not be the most interesting.

How does the weekly schedule of xkcd and What If play into that? Is it a way of forcing yourself to create with regularity?

If there's one thing I've learned from drawing xkcd, it's that I need a strict schedule. Some people who publish comics will just write whenever they have a good idea and put things up, without a regular update schedule. If I did that, I would never post anything. I have to have that deadline pressure to make me pick something.

And that was part of why I hesitated with the question-answering site, and part of why I picked it out of all the things I could have done a blog about -- because I knew that the questions were going to make me want to answer them anyway.

What about your work environment? Where do you actually do your research and your drawing?

For a long time, I was working from home. Once I got married, I started working from an office. I found that having somewhere to go that isn't my house is mentally helpful: "This is the place where I answer email and write blog posts," and "over there is the place where I do the dishes." Because otherwise, if I'm sitting around, I can go, "You know, I haven't cleaned the floor of the bathroom for a while." If you ever come to my house and the bathroom is clean, it means that I have some project I'm supposed to be doing that I can't get started on.

There are a lot of people who have written books about creativity that I haven't read, so I'm not by any means an expert on it, but my impression is that being creative is just a combination of getting new stimulus, but also having periods where you're not getting any stimulus. I had to stop reading Reddit sometime a few years ago, because I found that whenever I'd bump into a problem that was going to take a little time to solve, I'd just switch over and refresh Reddit and distract myself. Depriving myself of that has definitely been an important part of actually getting anything done, ever.

But at the same time, if you're just staring at your room with no Internet or no connection, you just go crazy and don't have anything to give you any ideas at all. Comics, once they start touring, all their jokes are about airplanes. So that's something I try to remember: Don't do all of your jokes about running a website.

But the jokes -- not just visually, but in tone -- feel consistent at the same time. I was going to ask you how the comic has evolved, but I guess the better question is: Has it evolved? Or would you say it's kept a steadiness throughout the years?

I don't know. I try not to spend too much time interpreting my comics for people, because I try to put out there whatever I can, and people can draw whatever conclusions they want. And if they like something and laugh, it affects how I think about it -- and maybe I do more of those, and understand what sort of jokes make people laugh, and so on.

The one thing that I didn't anticipate at the beginning was how much fun I had doing infographics. I think the things I've had the most fun creating -- and that have been the most invigorating and rewarding -- have been things like the chart of the movement all the characters in Lord of the Rings. That was one of those things where I'd always thought, "You know, it'd be so cool if someone could make that and see what that looked like." And since I'd been doing xkcd, I realized, I had a platform where I could do it.

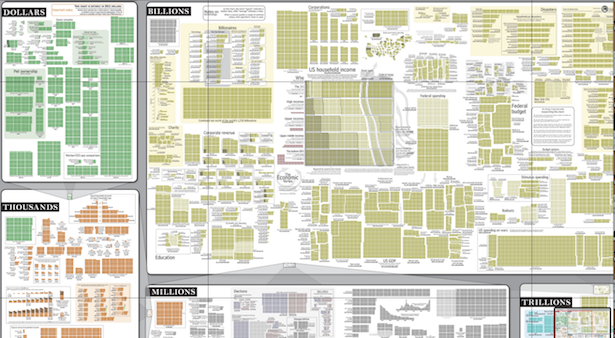

And last year, I did a chart of money and all these different amounts of money and all the different amounts of money in the world and how they compare to each other. It was about a month and a half of sixteen-hour days of research. I had easily ten times as many academic journal articles and sources on that one comic than on anything I did in the course of my physics degree. And the comic was so large, it wound up being a huge, sprawling grid. It was sort of disorganized -- I was going for this "Where's Waldo?" feel, where you could look through it, and find all this different stuff here and there. We printed up a version that was normal poster size, 24 x 36 inches, and then we got a billboard printer to make a double size version that was like six feet high, just so you could read all the little text.

That was a fun one. I don't really know about the "what is and what isn't a comic?" debate, but it's quite a stretch to call that a comic. I think it was comic #980, which I know because we had to do a lot of custom work for that comic to make it so people could drag and scroll and zoom in on it -- because there was no way that we could fit the whole thing on one screen. So I remember the number from having to load it up and test features to it.

So it lives in your heart.

Yeah. A lot of people will refer to comics by number to me, and I'll realize they're expecting me to remember all the comics by number. And I can't even remember what I ate this morning, let alone which comic was #473! What will also happen is that I'll have a joke that I'll make to friends, and then eventually I'll think, "Hey, that could be good as a comic." But then the next time I go to make that joke, with a new person, they'll be like, "Why are you quoting your comic to me?"

"Nooo! I'm not being pretentious, just forgetful!"

Exactly. I'm just one of those people who can always tell the same story twice, forgetting that I've told it already.

So, given the challenges of creating fresh content -- and I know you get this all the time, but I have to ask -- how do you actually come up with new ideas? Especially over such a long stretch of time?

I think, if anything, it's noticing the things that make me laugh and grabbing onto them and figuring out how to write them down. There are definitely times -- and I think this is pretty common among cartoonists -- where you spend an entire day trying to think of an idea, and you're like, "I give up." And then you go and take a shower or run an errand, and halfway there you get an idea.