View a high-resolution version

UK medical charities have warned that universities are being forced to reject their research grants because of a lack of government financial support.

Money could instead be given to universities abroad if the decline in state funding for science continues, according to the charities, with just over two months until the government’s spending review determines the level of research funding until 2020.

When medical charities award money to universities, they generally cover only the direct costs of a research project, but not overheads such as electricity bills or lab maintenance.

Since 2008, the Higher Education Funding Council for England has provided the Charity Research Support Fund to cover this gap. It adds around an extra quarter to charitable grants.

But as with the rest of the research budget, it has been frozen in cash terms at £198 million a year since 2010, and meanwhile charitable grants have grown in size. Research institutions have expressed concern that it is becoming “more and more difficult” to cross-subsidise this gap.

Aisling Burnand, chief executive of the Association of Medical Research Charities, said that a poor settlement for science in the spending review could mean that “universities will not consider taking charitable grants” because they cannot afford to cover the related overheads.

“They will always accept funding from the larger organisations but the challenge is whether they will accept funding from the smaller charities,” she said.

“They may end up being rejected…that’s already happening in some institutions,” she said, adding that a failure to address the problem “could really impact on the range of diseases that are researched”.

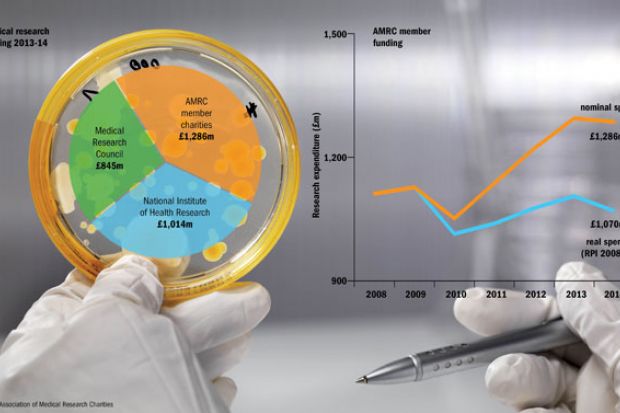

In 2013-14, charities funded more medical research than either the Medical Research Council or the NHS, according to figures released by the AMRC. But for the first time in four years charitable grants fell in 2013-14, dipping slightly to just under £1.3 billion.

This could be due to the “tough financial environment” or could simply be a “blip”, Ms Burnand said. “Some of the larger charities are planning to increase their spending” but this was dependent on the results of the spending review, she added.

As the funding gap grows, some members of the association have already been spending their research funds overseas, she said. This trend had not necessarily increased in the past five years, she acknowledged, but “if universities’ money declines then we will look abroad”.

Nicola Perrin, head of policy at the Wellcome Trust, said that the organisation “wouldn’t fund the full economic costs” of research in universities and said that it was “important to us that it’s a partnership with government”.

Around 20 per cent of the trust’s funding is already spent outside the UK. “We can decide where we invest, and we are more likely to invest in the UK if there is government support for the science base,” she added.

Asked what would this would mean in terms of the spending review, she said that another year of the same funding in cash terms “may be” acceptable “but [we] would want to see an upwards trajectory going towards 2020”.

Along with other heads of government departments, business secretary Sajid Javid has submitted modelling to the Treasury to illustrate how he might cut 25 or 40 per cent from the department’s budget. Mr Javid has been rumoured to favour the higher level of cuts.

In its submission for the spending review, the AMRC highlighted the growing difficulty of taking charitable funding for two research organisations: the Institute of Cancer Research and the University of Oxford.

Barbara Pittam, registrar at the ICR, told Times Higher Education that finding money to cross-subsidise charitable grants was a “massive problem”.

Income from fundraising and royalties was currently helping to cover the shortfall, but this meant that the institute did not have the ability “to invest in the future” and buy “new buildings and state-of-the-art equipment”, she said.

The situation is “not sustainable”, according to the AMRC’s spending review submission.

At Oxford, the biggest university recipient of charity research funding in the UK, more medical science divisions have started to run deficits over the past five years, with the real-terms reduction in the CRSF playing a “large part” in the deterioration of their finances, according to the AMRC report.

“Although not a disaster yet, it is becoming more and more difficult to fund this gap,” according to evidence provided by Richard Liwicki, deputy director of research services at Oxford.

Read David Matthews' blog on how to solve the charity funding gap

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Charity research grant? Thanks, but no thanks

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login