The Soviets’ Cold War Choreographer

Unlike the famously expatriated George Balanchine, Leonid Yakobson remained in the U.S.S.R. How his spirit is revitalizing ballet today.

To create modern art in a classical mode is to face forward and backward at once, yoked to the past while inching toward the future. Only a fool or a genius would attempt it. So I had heard of the Soviet ballet choreographer Leonid Yakobson, whose modernist advances took place on hostile home territory. I had seen Vestris, the solo he created for a young Mikhail Baryshnikov that compressed an early ballet master’s mercurial life into a few minutes; it was the only contemporary work the superstar brought with him when he defected in 1974. I knew that the best dancers in Leningrad and Moscow had deemed the choreographer a God-given genius and a rebel to boot.

But whom did these artists, trapped behind the Iron Curtain, have to compare him with? Their praise could easily be dismissed as nationalist hype. After all, the standard American view is that the Soviet vanguard of ballet barely outlived Lenin. The ferment was in Paris, where the young Russian émigré George Balanchine collaborated with Stravinsky on the groundbreaking Apollo for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Then the action traveled west, with Balanchine. Thanks to him and his New York City Ballet, angular, plotless, modernist works replaced silly story ballets as the art form’s pride. Without Balanchine, the thinking goes, ballet would have buried itself in the past—and indeed, since the master’s death, in 1983, it has struggled to chart a future.

In Like a Bomb Going Off: Leonid Yakobson and Ballet as Resistance in Soviet Russia, Janice Ross soundly rejects this self-congratulatory and ultimately self-defeating account. A dance scholar at Stanford, she delivers on her claim that “during the initial years of the Cold War, the West did not have an exclusive purchase on experimentation in dance.” The book’s timing could not be better: for the past decade or so, the Russians have been rehabilitating works from the Stalinist era that brilliantly debunk the notion that Soviet ballet slept out the 20th century. And Yakobson is the ideal figure on whom to focus a corrected and expanded ballet history. Other choreographers also experimented fruitfully and were periodically squashed by the state, and their work might have been even better. But the Leningrad Jew who was raised with the revolution, and who died before its whole edifice collapsed, is the peerless Balanchine’s perfect complement—the yin to his yang. Enlarging the parameters of ballet that Balanchine laid out, Yakobson’s example justifies the ecumenical spirit spurring on the art form today.

Both Yakobson and Balanchine were formalists. Both understood choreography in essentially modernist terms—as a process of distillation, or “abstraction,” as it is more commonly known. But Balanchine began with the danse d’école, the movement lexicon inherited from the French court, while Yakobson started with the world, even if that meant setting the women’s pointe shoes aside and abandoning the standard turnout of the leg. Russian Orthodox to the end, Balanchine often presented the classical idiom as a veil through which to glimpse the metaphysical. The secular Yakobson saw ballet as a chance to illuminate our irrepressible natures and the eccentricities they breed. For an artist living through the most-repressive years of the Soviet regime, ballet’s penchant for idealization held no appeal: it reeked of ideological obfuscation. Feisty in temperament and fearless on principle, Yakobson homed in on what the Marxist marching orders “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” left out: unaccountable want.

Leonid Yakobson was born in St. Petersburg in 1904, the same year—in fact, the same month—as Balanchine. He too left home early, not to become a ward of Theater Street, as Balanchine did, but simply to eat. With the civil war spreading famine, his widowed mother sent her three sons to a children’s summer colony that promised food. But hunger and panic soon overtook the idyll, and caretakers fled. The children wandered until the American Red Cross gathered them up to transport them to Vladivostok, on the Pacific Ocean. The summer stretched into years. When it was finally time to go home, the weary tribe traveled by sea—15,000 miles.

Who knows why Yakobson lit on ballet upon his return, except that he liked to dance. At 17, he was much too old to enter directly into the state school, so first he trained for three intensive years at the private studio of a renowned character dancer with the former Imperial Ballet. Learning ballet fundamentals from a character dancer is a bit like studying classical music with Thelonious Monk: you’ll always see things slant. As a Jew in a country whose switch to socialism did not curb its violent anti-Semitism, Yakobson might have already inclined that way.

Like the comic interludes in Shakespeare peopled by gravediggers and rude mechanicals, character dance comments on the drama while seeming to digress. And it speaks in the unruly vernacular: folk dances from the wilds of Poland and Italy, the antics of juggler and clown. Ballet proper—the domain of heroes and their backup bands—has its piquant aspects: the plucky pointe work, the sprightly jumps. But in the Russian tradition, the more virtuous you are, the more smoothly and grandly you move. Other than adding proletarian muscle, Soviet ballet preserved this formula, including the populist counterpunch to the heroics, the character dances.

Until Yakobson’s final years, when he was granted his own troupe, his career unfolded mainly in and around Leningrad’s Kirov Ballet (now the Mariinsky). But it was probably his sojourns in far-flung republics during the 1940s that cemented his commitment to character dance. His task was to flesh out the dictum “National in form, socialist in content” by adapting regional folk dances, ethnic fairy tales, and village customs to the stage for every citizen to enjoy. He was hugely successful. The evening-length Shurale is still touted as a Tatar national treasure. Miniatures he ghostwrote for a Moldavian folk troupe—dance cosmos bursting into light, then vanishing, within 10 minutes—continue to be part of the curriculum at the Mariinsky’s legendary school.

But just as Dylan rewired folk, Yakobson—the singer-songwriter’s equal as artist-sponge and “cultural ventriloquist,” in Ross’s apt phrase—updated character dance. He distilled it down to its constitutive parts, to the feelings and impulses that harmonize as personality. The Kiss—one of a series of miniatures inspired by Rodin sculptures—uses shuddery steps to anatomize the waves of anticipation and reaction that emanate from kissing communicants. To convey the exhilaration of the waltz, Vienna Waltz exaggerates the dance’s upward lilt. The man suspends the woman overhead so she resembles a downward-swooping lark; he sends her cartwheeling through the air with her ruffled dress fanning out like a sail. Yakobson does to emotional experience what Cézanne did to a pear on a table: he breaks up the smooth-seeming surface so we see it anew.

To find a like-minded modernist, you would have to look beyond ballet. Besides the rough-edged Rodin and Cézanne, Yakobson’s artistic kin include the 20th-century modern-dance maverick Martha Graham, with her highly stylized language for forbidden feelings, and the Soviet theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold—the inventor of biomechanics, by which the actor physicalizes every immaterial impulse to eerie and jolting effect.

Jerome Robbins, acclaimed for his work on Broadway but forever in Balanchine’s shadow at the New York City Ballet, once complained that ballet was the “ ‘civilizationing’ of my Jewishness.” Yakobson reversed the nouns, Jewishnessing civilization. In place of 19th-century nobility of manner or hunky Soviet stalwartness, he insisted on what the novelist Joseph Roth, recovering from a night at the Moscow State Yiddish Theater in 1926, designated the “Dionysian Jew”—by turns inflamed with passion, savagely melancholic, fanatically grieving, and dizzyingly joyful. “Every idea of the proverbial vitality of Jewish people you may have brought to this theater,” the shaken Roth attested, “was outdone.”

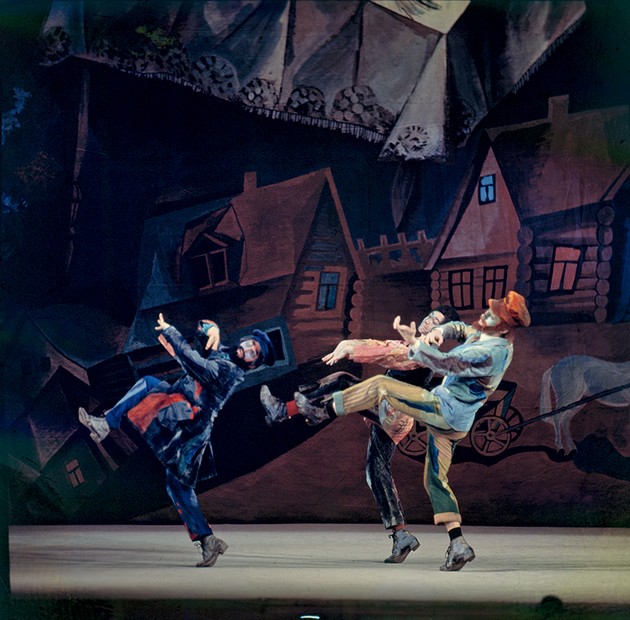

Dionysian Jew is the same kind of oxymoron as dancing your heart out: it binds frenzy to custom, lending legibility and power to passion. Yakobson seems to have understood how fundamental to ballet this paradoxical union is, because he chose stories and themes that brought it to the fore. In the thoroughly delightful fairy tale Shurale, a drunken husband and wife stumble home from their son’s wedding in a blur of exultation and renewed love—and in time to the music, a significant departure from the pantomime that traditional ballet would have enlisted for such a scenario. Their drunken steps are as patterned as their happiness—the memory of earlier weddings and the likelihood of later ones ringing round the present joy. And around that are all the other Tatar traditions that Shurale invokes. Facing backward to ritual and forward to the giddy moment, Yakobson met the daunting challenge of modernist ballet again and again.

In the decades following Balanchine’s death, ballet seemed to have reached a dead end. His heirs understood formalism as the most forward-looking and imitable of his many modes, but they didn’t appreciate how much its power depended on the spiritual yearnings and existential wisdom with which he infused the steps. Their work was dogged and desiccated, full of moves that signified nothing. What has finally lifted ballet out of this rut and made its future bright again are choreographers with mixed lineages—bastards of history who couldn’t repeat the past even if they wanted to, because there isn’t just one to repeat.

Yakobson could have predicted this fortuitous turn of events. If his story has a moral, it is that there are many roads to ballet’s future and none of them is paved.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.