Resilience

The Truth About How to Develop Robust Resilience

Kurt Lewin's grandson explains the social nature of resilience.

Posted July 19, 2017

Following the publication of our co-authored book, From Breakdown to Breakthrough: Forging Resilient Business Relationships in the Heat of Change, I sat down with principal author and organizational development consultant Michael Papanek (the grandson of pioneering social psychologist, Kurt Lewin) to unpack the difference in his approach to resilience:

Liz Alexander (LA): Michael, what is your definition of resilience and how does that differ from other, more individually-focused definitions out there?

Michael Papanek (MP): I see resilience as a social structure that we create and invest in, which then allows the people within that structure to thrive and innovate under adversity, change or stress. While individual resilience is good, I think social resilience, based on relationships, is necessary for the level of change we are seeing in the world now.

LA: Why do you say that resilience should be considered a social phenomenon, rather than an individual trait?

MP: All complex issues today need social solutions, and creating and sustaining anything of real value always needs a team that can persevere through barriers. While we must each take care of ourselves, some changes are so big that no one can expect to succeed on their own.

LA: With respect to the three components of resilient relationships that you outline in your book -- strong, flexible and fair -- can you give us one example and a practical tip for developing each of those parts?

MP: "Strong" means creating value through the relationship. One tip is to be clear as to how your customer or colleague sees the value they gain from the relationship. It might not always be what you intend or think it is! Look for multiple and unique ways to add value and you will have a more resilient relationship.

With respect to flexibility in a business relationship, this involves approaching change as an "action learning" opportunity. Rather than expecting to implement new things perfectly from the onset, frame the change as experimental, involving learning. Then scale up only when you have established proof that your approach works. In this way you can test innovative ideas and control the business risk at the same time.

The roots of fairness -- the third component of resilient relationships -- means making sure that each person or group's contribution to the team effort is being rewarded, that they feel they have permission to be true and honest in the relationship, and that each person feels respected. If you need to increase fairness, look for opportunities to act on others' suggestion or ideas, ask for feedback and respond to it. Then do an "audit" of the inputs and outputs to make sure they are in line.

LA: You suggest that one cannot expect to create resilient groups with only one or two of these three components (strong, flexible and fair) present. Why is that and how do we ensure we're leveraging all three at once?

MP: The essential "engineering" definition of resilience is a combination of strength and flexibility, like a palm tree that can bend but doesn't break during a hurricane. The problem with this is that humans are not trees. We also have emotions, values and interests that are important to us; we need respect, trust and honesty.

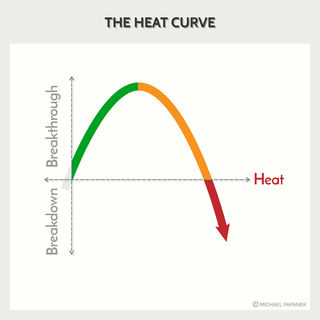

So only the combination of all three can successfully produce resilient relationshps that stand the test of time. Not just when the environment is supportive and straightforward, but when the going gets tough and the "heat" is on. After all, it's relatively easy to maintain good relationships when facing few challenges. The key here is to understand how to ride what I call "the heat curve" (see left).

The primary advantage of creating resilient relationships is this: the more resilience you have, the higher you are able to ride the heat curve and leverage the benefits of increasing success, without the costs.

Indeed, only by first developing resilient relationships that are strong, flexible and fair, can leaders ensure that the rising curve of breakthrough is sustained far beyond what could normally be achieved.