Source: Alamy/Getty

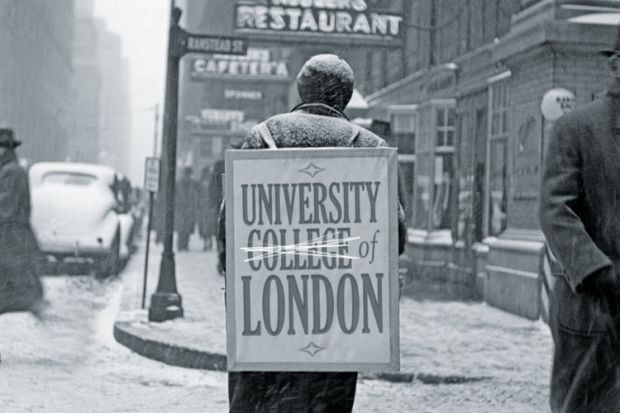

Making a name: it takes a lot more than a few chosen words to establish and maintain a reputation

Use ‘London’ in your title

Although it is more than 400 miles away, a photograph of London features on the home page of Glasgow Caledonian University’s website. Marketing gone mad, you ask? Not quite: it has a postgraduate campus in the nation’s capital. GCU London specialises in finance, fashion and marketing, and opened in 2010.

Increasingly, institutions a little closer to the capital are also including London in their name. Thames Valley University became the University of West London in 2011, Brunel University added London to its title last year after gaining permission from the Privy Council, and others that use the capital in their title include Kingston University and Middlesex University.

According to Paul Temple, reader emeritus at the UCL Institute of Education, adding London to a name suggests that an institution is part of the illustrious Golden Triangle with Oxford and Cambridge. It also evokes the glamour and culture unmatched by any other UK city, in an effort to hook prospective international students and British countryside dwellers alike, he said.

Imitate Hogwarts

Maximise the history. Students love institutions with pedigree: the older, the better. The websites of the universities of Durham, Edinburgh and Newcastle are littered with images of their oldest buildings. So much so, that you could be forgiven for thinking that the entire city around the university is ancient and ornate.

In the past decade, it seems, modern universities have gone out of fashion. Winston Kwon, Chancellor’s fellow in strategy in the University of Edinburgh’s business school, suggests that the popularity of the Harry Potter books has played a part in the shift, with J. K. Rowling’s work offering a fantasy-world remix of the Oxbridge aesthetic. Dining halls with vaulted ceilings impress applicants looking for a “traditional” education, which tends to correlate well with strong performance in the league tables. Adopting a traditional coat of arms, a Latin motto, and if possible a castle, will surely make those Ucas applications come flying in…by owl, of course.

Names are not everything

Assume that anyone applying to university realises that institutions’ names are illogical. International applicants will probably be familiar with the set-up in the US, which is even more of a minefield, as the terms “college” and “university” are used more or less interchangeably. Although Queen Mary University of London dropped “college” from its official title (Queen Mary and Westfield College) when it legally changed its name in 2013, Kwon observes that the difference was simply semantics: changing a college to a university makes no difference.

Instead, he contends, sometimes vice-chancellors and provosts may be meddling for the sake of it. “It’s easy for people at the top to forget what the market is like,” he says. Prospective students look at subject league tables first, and opt for the best institutions they think they have a chance of getting into. Where King’s College London or University College London feature, students are unlikely to mistake them for further education establishments.

Sound as British as possible

The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge have worked wonders for their alma mater, the University of St Andrews. Guests paid as much as $10,000 (£6,400) a ticket at a recent fundraising dinner in New York attended by the royal couple, and the ensuing publicity was impressive. Attracting a royal is a challenge, however, and it will be 15 years or so before Prince George starts to consider his options.

But adopting a regal-style name is a relatively easy way to woo the international crowd. Royal Holloway, Queen Mary and Imperial all sound royally English, something the likes of the University of Westminster and Regent’s University London (which cannily also has the capital in its name) may have tried to emulate. The allure of quintessentially British words can also be seen in the countless private colleges namechecking illustrious figures ranging from Churchill to Nelson in their efforts to attract students, particularly from overseas.

Get everyone on board

Humiliating petitions, tweets and angry emails have succeeded in getting hastily conceived rebrands ditched.

Students at King’s College London set up an e-petition in December to stop the institution’s rebranding plans, which they labelled “bizarre”. They added that the change would “undermine almost 200 years of tradition” at “huge and unnecessary expense”. More than 12,000 staff, students and alumni signed the petition, and just over a month after the protest was launched, King’s ditched its plans.

Thousands also “liked” a Facebook group calling for Leeds Metropolitan University to keep its name, but to no avail – it was reborn as Leeds Beckett University in 2014.

Although universities frequently see rebranding as a way to indicate improvement and progress, alienating alumni risks reducing donations and could leave institutions with a worse reputation than before.

So how much will it cost?

Expect a six-figure bill to change a name, advises Kwon. It depends how ruthless the rebrand is, but costs can spiral quickly.

The ill-fated King’s College rebrand was said to have cost £300,000. King’s wanted to drop “college” from the name because research revealed that it was causing confusion among prospective students. When Leeds Metropolitan University reinvented itself, the exercise was thought to have cost £250,000, according to media reports.

Speed can be a crucial factor in rising costs: getting new headed paper at short notice, for example, will be more expensive. But if the need for a rebrand is really because the institution needs new management, taking on a new vice-chancellor might double the bill. “It can be important to change the vice-chancellor, whatever has gone wrong,” Kwon says. And vice-chancellors don’t come cheap… some earn more than £400,000 a year.

And finally – are you sure?

According to Kwon, “Rebranding on its own is like putting a new coat of paint on an old house. If the house has been thoughtfully updated, then the paint is a symbol of that, and will resonate with the target audience.” However, “if it is just a coat of paint on a tired structure, then people quickly see through it because the message doesn’t resonate”.

Instead, he says, a university should consider why it is slipping in the market. Pitching to the right audience is vital: is it aiming at the upper end of the market when perhaps its research quality is slipping or its student accommodation is ageing? Fiddling with the typeface or logo will not fix either problem.

Instead, universities should focus on maintaining their relative position in the market, and not attempt to rebrand. “Brand image is an indicator, but not a cause, of market positioning,” Kwon says.

Harriet Line

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login