The Mysterious Vanishing Brains

How could 100 jars of human brains—taken from deceased patients of an Austin mental hospital—just disappear from their home at the University of Texas?

Somewhere in a little-used room in the bowels of the Animal Resources Center on the University of Texas’s campus in Austin sit around 100 or so large glass jars. They’re stored three-deep on a wooden shelving unit that takes up an entire wall. Glass doors do a fairly good job of keeping off the dust and protecting them from the occasional visitor to this air-conditioned storeroom.

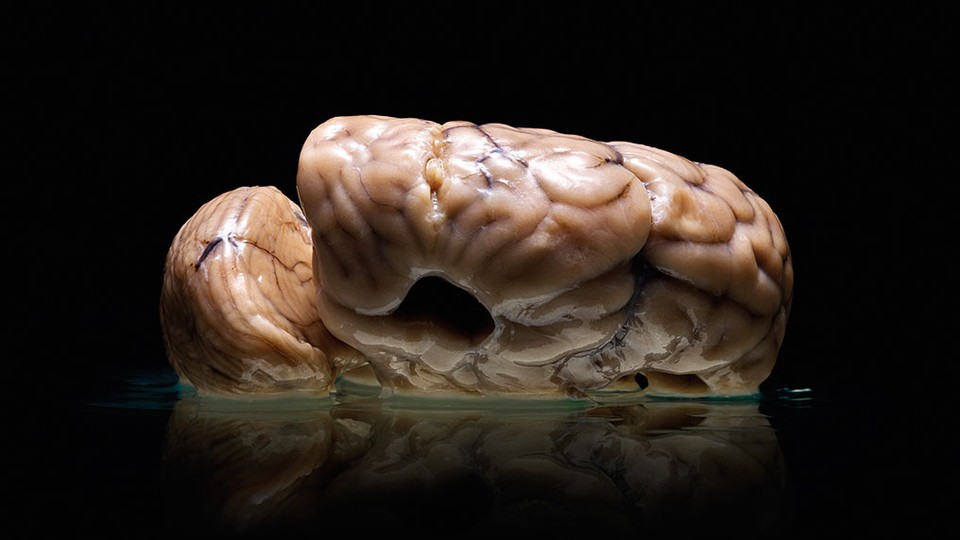

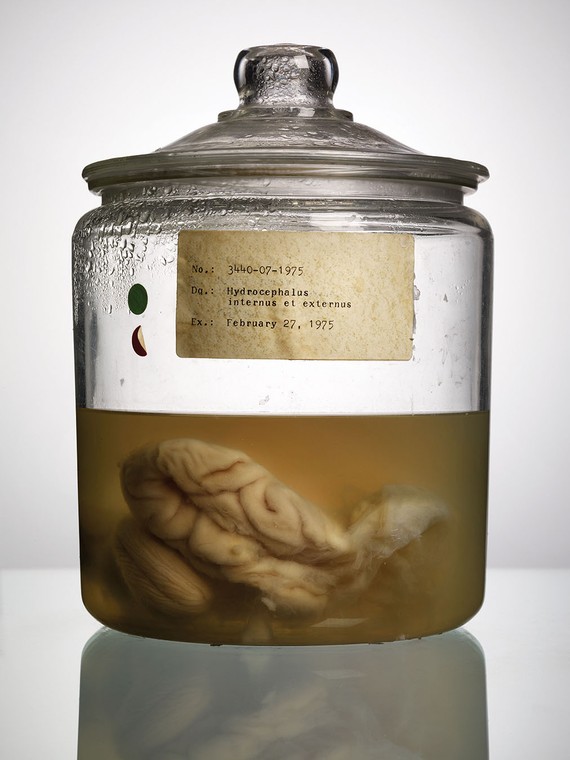

Those jars house an unlikely collection: Each contains a complete—or, in a few cases, a partial—human brain, submerged in formalin. And on most is affixed a label, faded with time but still legible, inscribed with three pieces of information: a reference number, the condition from which the patient suffered (described in archaic Latin), and the date of death.

The specimens, which date back to the 1950s, all belonged to patients at the Austin State Hospital (ASH), formerly the Texas State Lunatic Asylum, an institution that still sits on a shady lot off Guadalupe Street, about three miles north of downtown Austin.

One jar labeled “Down’s syndrome” seems to contain more than one brain and possibly other internal organs. Others hold brains along with flaps of skin known as dura, the leathery tissue that covers the inner lining of the skull.

Translating the Latin descriptions opens a small window into the worlds these patients inhabited, hints at the suffering they must have gone through and the sometimes painful deaths they probably endured. It’s unsettling as a number of the conditions are at least manageable, if not treatable, today: Apoplexia cerebri, where a burst blood vessel or stroke would have caused a sudden malfunction of the patient’s brain; Hemorrhagic subarachnoid idle frontotemporal, a bleeding between the brain and the skull in the frontal temporal area.

The history of the Austin State Hospital is fascinating. According to historical documents, in the 1800s the grounds of the asylum were enclosed with a substantial cedar fence, and patients helped tend the fruit orchards and vegetable gardens. If you visited the grounds back then, you’d have seen patients pacing along paths cut between the stately oaks or sitting on one of the numerous benches. Some worked in the farm or shops—said to be a part of their therapy.

The men and women whose brains now sit in jars in the Animal Resources Center at the University of Texas would have experienced the ups and downs of life at ASH, specifically the turmoil that it went through in the 1960s and 1970s: the overcrowding, the experiments with different forms of treatment (from fresh air and gardening to Thorazine and electric-shock therapy). And they’d also have experienced a life effectively shut off from the outside world, in their own little town.

From the 1950s to the mid-1980s, the resident pathologist at the hospital was a man named Dr. Coleman de Chenar, and it was in the room where he performed autopsies that he began to amass a collection of brains. At the time of his death in 1985, he had around 200 specimens that he’d collected during routine autopsies on mental patients.

Space at ASH was limited, and the hospital was keen to find a new home for de Chenar’s peculiar collection. According to a story in the Houston Chronicle in 1986, the search for a new home for the collection began because ASH couldn’t legally dispose of the formaldehyde in which the brains were preserved. Linda Campbell, then-director of Clinical Support Services at ASH, told the paper that she had been overwhelmed by calls—including from six major institutions that wanted the collection. She said the specimens were a valuable research tool, offering an inside look at how diseases attack the brain.

Harvard wanted to expand its already sizable “brain bank,” which at the time had more than 1,000 specimens but few from schizophrenic patients. “There is so much information available in those brain tissues, and so many researchers are crying out to get such tissue,” Dr. Edward D. Bird, an associate professor of neuropathology at the school, told the newspaper.When it was bequeathed to the University of Texas (UT) in 1987, the Houston Chronicle reported that UT had beaten Harvard Medical School, among other institutions, to the collection. It was described as the “battle for the brains.”

Among the 200 or so brains trucked from the Austin State Hospital campus just down the road to the Animal Resources Center at the University of Texas was one that would raise eyebrows among the few people who got the chance to see it. This one belonged to Charles Whitman.

On August 1, 1966, Whitman, a 25-year-old engineering student at UT, took an elevator to the observation deck of the University of Texas Tower—a 307-foot-tall structure a scant few miles south of ASH that has become the college’s most distinguishing landmark—carrying with him guns, food, and ammo. A former Marine sharpshooter who had never before committed a crime, Whitman then began methodically shooting people at random with a high-powered rifle: students walking to class, random shoppers, even a man sitting in a barber’s chair.

Ninety-six minutes later, Whitman was fatally shot by police officers. At end of his deadly shooting rampage, he had killed 16 people and wounded 32.

Police later discovered that the night before the shooting, Whitman had gone to the apartment building where his mother lived and stabbed and shot her to death. Later that night, he stabbed and killed his wife as she lay sleeping in their bed.

What would became known as the Texas Sniper shootings is considered one of the worst mass school killings in American history. After his death, Whitman’s body was transferred to the Cook Funeral Home, and an autopsy performed on his body by Dr. Coleman de Chenar, the ASH pathologist. Whitman had actually requested the autopsy himself in a note he left behind for police to find, urging physicians to examine his brain for signs of mental illness. He had sought medical advice several times in his lifetime, suspecting mental illness as the culprit for his severe headaches and intense feelings of hostility, but he was never formally diagnosed with any condition.

Chenar noted in his brief report that Whitman’s skull was “unusually thin.” He pointed out various fractures in the skull, a splinter in the temporal bone, and bleeding—all of which were a result of the police officers’ rounds of bullets—but in the middle part of Whitman’s brain, the pathologist found a five-centimeter-long tumor. At the conclusion of the study, Whitman’s brain was returned to ASH, where it reportedly ended up in the collection of specimens then housed at the hospital.

Fast-forward almost 50 years and we’re inside the Animal Resources Center checking every labeled specimen in the collection of archaic brains. But Whitman’s isn’t there. There are other brains—sliced and diced and in jars without labels. Could these be parts of Whitman’s brain that the report says was dissected in de Chenar’s original autopsy the day after the killings?

Whitman’s, it transpires, wasn’t the only brain missing from the collection. Tim Schallert, a neuroscientist at UT and the collection’s curator, says that when the original brains were bequeathed to the University of Texas, there were around 200 specimens. By the mid-1990s, they were taking up much-needed shelf space at the Animal Resources Center, and Dr. Jerry Fineg, the center’s then-director, asked Schallert if he would move half of the jars elsewhere.

When Schallert got around to it, he says they had vanished. He asked Fineg if he knew what had happened to them, and Schallert says Fineg told him he got rid of them. “I never found out exactly what happened—whether they were just given away, sold or whatever—but they just disappeared.”

Fineg, a veterinarian whose pioneering work with chimpanzees in NASA’s space program helped prove humans could survive in space, retired from UT, and as director of the Animal Resources Center, in 2006.

I asked Fineg in a telephone call whether he recalled what had happened to the missing brain specimens. He said the last he heard was that they were sent back to the Austin State Hospital. “They were in storage in the addition to the Animal Resources Center—not the original building, but the new one. All the brains were stored there, but we ran out of room and we told them they had to get them out of there, and that’s when they gave them back to the state.”

Fineg said Tim Schallert made arrangements to have them sent back to the Austin State Hospital.

Schallert, though, said he didn’t send them back to the hospital at all. A spokesperson at ASH confirmed this, saying once the specimens were donated to the university that was the last they saw of them.

A few weeks later, Fineg wrote in an email to me: “I have been racking my BRAIN trying to remember where those brains went and although ASH says they know nothing about them I still believe that is where they went ... SORRY.”

It’s a mystery worthy of a hard-boiled detective novel: 100 brains missing from campus, and apparently no one really knows what happened to them. Going through the official channels at the University of Texas eventually leads to a suggestion that Tim Schallert might know, as he is the collection’s curator. It’s back to square one.

Back in 1986, the Houston Chronicle described a fierce “battle for the brains” between UT and Harvard Medical School, and now 100 of the specimens—half of the original collection—have disappeared. Space at UT was limited, but the director of clinical support services at the State Hospital 25 years earlier had described being “overwhelmed” by calls about the collection. They were, she said at the time, a “valuable research tool.” A Harvard professor had said researchers were “crying out” to get the brain tissue in the UT collection. And yet today, apparently nobody knows where half of this valuable collection has gone. Were they given back to ASH? Were they sold? Were they given away? Will we ever find out?

The article has been excerpted from Alex Hannaford's Malformed: Forgotten Brains of the Texas State Mental Hospital.