Picture this. You're deeply engaged in one of the many free-to-play adventure games available online, when you decide to buy a bigger sword. It could be that you made the tactical decision to extend your armoury, or that you panicked when you spotted a gigantic dragon lumbering in your direction; you might not even know why you did it. You just fancied a bigger sword. But that action took you into the barely two percent of free-to-play gamers who actually pay for content – and the game makers want to know why.

The freemium gaming business is expanding rapidly. We all know about the Facebook behemoth Zynga, which now claims over 250 million monthly players, and is valued at anywhere between $5-10bn. But online, there are dozens of global companies hawking a range of in-depth gaming experiences. There is the German publisher and portal operator, Bigpoint, which runs massively-multiplayer browser games like Legend: Legacy of the Dragons and Battlestar Galactica Online and claims over 150 million subscribers. There is Korean veteran Webzen, with its long-running fantasy role-player Mu Online, which alone boasts 56 million users. Beyond these giants, there are dozens of new freemium social, browser and smartphone games starting up every month, looking to gain a foothold in the densely crowded market.

And what the big players have learned is that coming up with a great game concept is only the beginning. A successful free-to-play game is all about inspection and iteration; it is about launching quietly, testing and fine-tuning the experience constantly, watching how players react, listening to feedback and re-building. This is how the likes of Popcap and Playfish arrived at super-addictive titles like Fifa Superstars and Plants vs Zombies. And now a whole new business is emerging to help developers understand their players.

Alan Miller has been in the games business for over 30 years. He was one of the first programmers to join Atari's home console business, and he later co-founded Activision, currently the world's largest third-party games publisher. For the last decade, though, he's been working in the online sector, including a stint working on advergames with fellow Atari legend David Crane. Earlier this year he joined GamesAnalytics, a new UK-based company specialising in the data-mining and monetisation of online games. It's a real-time service that continually monitors every player in any virtual world it's commissioned to work on. It's like CCTV constantly monitored by psychologists and statisticians.

"Our objective generally is to increase monetisation and improve player satisfaction," he explains. "Usually, the publisher's objectives have to do with increasing revenues, but not always. Sometimes they want to increase the virality, the number of invites and notifications sent out from a game. Then we look at their data and we identify behaviour patterns. It allows the publisher to learn a lot more about their game than they thought they knew.

In his experience, it's rarely great big design errors that trip up growing freemium games – it's tiny, often over-looked alterations. "We're working with a big MMO at the moment. We studied the last five years of their operations and we noticed that there was a huge change in just one month in the retention rate of new players. It turned out the publisher had made just one change that caused the game to be less appealing for newcomers - they didn't even notice it; this is one of their worlds! So now they're trying to digest that information and work out what they did wrong."

The key message behind freemium analytics is that free-to-play game construction is similar to web design – the publisher needs to understand, and subtly guide, every aspect of the user journey through the experience. Whereas traditional games are about creating big macro-environments for player exploration, freemium is about micro-managing every step the player takes toward actually buying something.

"A developer can build 'funnels' that depict the player actions leading to a financial conversion like purchasing extra content or virtual merchandize," says Justin Johnson, CTO of Playmetrix, another British company specialising in game analytics. "It's then down to the developer to use this analysis to improve conversion by removing obstructions and bottlenecks that may be inherent in the design. For example, aspects of the game may be unclear or too difficult for newcomers, leading to early high attrition, which means they never reach the purchase step. Our system also tracks the amount of money that a player spends giving metrics called ARPU (Average Revenue Per User) and LTV (Lifetime Value). Simply put, the LTV of a player must exceed their cost of acquisition for the game to be profitable."

It's a strange business. In the free-to-play universe, every player action is a potential metric in a revenue model. In-game behaviour is an algorithm that needs to be unraveled and de-coded. Developers have to operate like a sort of secret police agency, effectively bugging players – the Playmetrix software allows them to embed 'call backs' into their game code that trigger when players do something of interest. This is all visualised via graphics and charts so activities become infographics. It sounds kind of sinister, but understanding every intricate player activity is what makes a game in this sector successful. With no financial outlay at the beginning, players have much less impetus to keep playing; hence, 'funnel analysis' – tracking a player from the moment they register, though their actions in the game, to their first purchase. At any moment along this journey they may quit out. Understanding this is the key to lowering the dreaded 'attrition rate' – the numbers of people leaving the game.

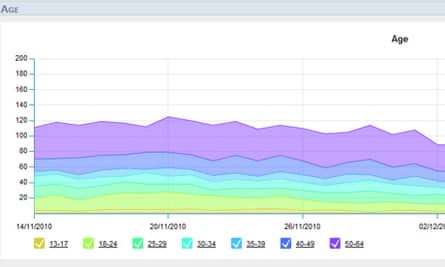

Another key element in the maths of social gaming is the DAU/MAU ratio. As Johnson explains, "most games have the base behaviours of attendance and engagement. For that, we track daily active uniques (DAU) and monthly active uniques (MAU). By taking a ratio using the two (DAU/MAU) we can determine the percentage of monthly users that play each day and also derive churn." Last year, Lisa Marino of Rockyou, gave a GDC talk entitled Monetizing Social Games in which she identified the minimum threshold for a successful DAU/MAU ratio as '.2'. That's game design reduced to a single figure.

But it's not just about data mining and statistics. Miller argues that good freemium analysts have to know about traditional game design too. "Let's say that in a certain MMO there are ten common behaviour patterns that ultimately result in players becoming paying customers. Clearly, our identification of these patterns won't account for every player, but they'll account for significant groups of players that went through the process. And we might discover that along the chain of events that lead to monetisation, the player has to, say, kill a dragon. Well, we can identify bottlenecks and say well maybe 89% of the players who tried to kill that dragon failed. Then we would advise the publisher to reduce the threshold. That's a combination of using the analytical tools coupled with our experience of game design to improve the situation for both the publishers and the players."

In short, the dragon fight might not necessarily have to be removed, or even made easier, but it needs to be sign-posted. Miller says the GamesAnalytics software can deliver in-game messages to players, such as hints, challenges, free goods or offers – all designed to motivate that individual to move along that pipeline to satisfaction and – in theory – revenue.

Johnson agrees that it's sometimes very slight in-game elements that can add to player churn. "The biggest mistakes are sometimes the most simple ones to make. For example it's easy to over complicate, over engineer or omit to tell the player what they're supposed to do next. Instructions may not be clear or a sense of progress, reward or player gratification may not come soon enough. It may be that a game's intro sequence is slightly too long which means a large number of new players get bored and turn to another game as a result. It's important to get the psychology and balance right so that the decision a player has to make in order to purchase is based on perception of value. If a game is confusing, incorrectly paced and doesn't have a clear sense of value in its monetisation plan then it's not going to do well."

Of course, GamesAnalytics and Playmetrix are not the only companies operating on this emerging sector – Kontagent is an analytics platform that provides data on social applications, including games, and Adobe's Omniture helps with tracking acquisitions. The big question, though, is why these companies exist at all. With player retention proving to be such a key role in social and online game design, shouldn't the publishers have their own analysts in-house?

Zynga certainly does – its dedicated team makes use of what is apparently the largest data warehouse in the world to track the behaviour patterns of its players. Sometimes it simply learns from how its users communicate. At this year's SXSW festival in Austin, the company's chief designer Brian Reynolds told how a tutorial level for the Frontiervillegame involved finding a sheep; when players achieved it, they had the option to post a cartoon image of a girl milking a ewe – except many players were amused that the crude image made it look as though the some sort of inter-species sex act was going on. The amount of chat it generated turned out to be a brilliant viral marketing tool, so Zynga went ahead and loaded the game's FaceBook messages with innuendo, such as 'Bob has some serious sacks' and 'Margaret needs a few good screws'. It was enormously popular. So there is science, there is data-mining, and there is the knowledge that middle-aged gamers like dirty jokes.

Popcap, the hugely successful developer of Bejeweled and Zuma, has its own system. As Bart Barden, the company's director of online business explains, "we have an analytics team in-house that studies player data from three perspectives. First we look at actual gameplay, which includes things like number of games played, average score, highest score and number of moves. Second, we analyse the social activity tied to the game, which includes how many times they share a score or power up on Facebook. And finally we look at monetisation, how people like to transact.

"Recently, in Bejeweled Blitz, we increased the frequency of players being able to get and receive special gems (like the Cat's Eye or Phoenix Prism) based on some data we saw surrounding sharing. We found that players were much more likely to share a special gem with their friends than any other event in the game so we responded to that. This change has resulted in better engagement, which is a win-win for both the player and PopCap."

Indeed, the company's mastery of the social gaming market has just led to its purchase by Electronic Arts for a whopping $750m.

So why isn't this sort of analysis part of every social or online game? Johnson reckons it's down to cost and time. "Some developers have rolled their own solution but they are generally ad-hoc and fairly crude. Producing meaningful analysis capabilities isn't trivial - segmentation, funnels and cohort analysis requires a lot of thought and before you know it you're dealing with scalability, uptime commitments and a whole host of technical and operational issues that are far removed from creatively delivering a game." He likens the use of third-party analytics software to licensing a 3D engine like Unreal – it's about freeing up time and resources within the development process.

It remains an esoteric, slightly sinister area for traditional gamers, though. Indeed, old skool publishers such as Activision and EA have found it just as challenging to evolve their thinking from the retail model into the freemium arena. Which is why EA bought Playfish in a deal worth up to $400m and Disney laid out $760m on Playdom – it's just easier to buy that expertise in. It's going to become more important though. With more and more games adopting the freemium model, actually understanding what hooks gamers into patterns of playing, sharing and buying will be a vital element. Barden reckons that, right now, third –party analytics systems are most clearly optimised for social titles based around resource management, but says their use will become more common, especially for small and medium-sized developers.

"Additionally," he says, "as more social game platforms emerge, third-party analytical toolsets become more valuable to consolidate and aggregate data across multiple social networks and products. The overall importance and focus on analytics will continue to grow over the next two or three years but how individual companies choose to act on that intelligence may vary."

The important thing to think about is that, in the free-to-play era, marketing and game design are indivisible – they're essentially the same thing. Players have to be on-brand and on-message, they have to be active agents in the game world and the advertising of that world. And everyone has to be watched. Although, all the industry people we spoke to were keen to point out that brilliant design is still the leading factor. As Miller puts it, "It's important to realise, we're not selling accountancy software. You're creating an emotional experience, it's an art form, individual style is tremendously important."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion