Tanya Seghatchian, co-producer/executive producer, Harry Potter 1-4: I started working with David Heyman at Heyday Films in 1997. We had a deal with Warner Bros to be the eyes and ears of the studio in the UK. I remember a friend of mine, Tony Garnett, who produced Kes, saying to me: "Listen, this deal will only last if you find Warners the equivalent of the Bond franchise." I read an article on a book that was due to be published, about a boy who discovers he's a wizard. It said it was going to be one in a series – so that's a franchise. I rang Christopher Little, Jo Rowling's agent, to introduce myself and win him over if I could.

David Heyman, producer, HP 1-8: When the proof copy of the first book came in, it sat for a few weeks on my bottom shelf – low priority.

Nisha Parti, production consultant, HP1: We'd been running the company for a while and hadn't found the big thing Warner Bros was hoping for. There was a slight gloom in the air about that.

DH: Each Friday, we'd decide what everyone would read over the weekend.

NP: I read the first Harry Potter at home on a Saturday morning. It was brilliant – a huge, original story which felt so visual and filmic. I came in raving about it on Monday morning. David asked what it was called and I told him: Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone.

DH: I said: "I'm not sure about the title." But I read it and fell in love; the world Jo had created was so rich. Warner Bros were not immediately enthusiastic.

TS: It was not a sure thing by any means. Family entertainment was not at the centre of film culture in the way it is now. For me, Jo's book was an adventure, but it was also about character and emotion and the power of love. I knew its appeal might reach more than just children.

NP: No one around London will admit that they read the book and passed on it, but I know through the grapevine that quite a few other big companies didn't see in the book what we saw.

DH: One of the first people we asked to direct it was Mike Newell, who ended up doing the fourth film. We asked Richard Curtis to write the screenplay, and he said he would do it if Mike directed; they had worked together on Four Weddings and a Funeral. But Mike turned it down.

TS: Steve Kloves wrote the screenplay, and Jo said the minute she met him she knew Harry would be in safe hands.

NP: There were lots of discussions about directors – Alan Parker, Terry Gilliam, Steven Spielberg.

DH: When Steve delivered his script, Spielberg read it and we had two long meetings. At the end of one, Spielberg showed me a picture of Haley Joel Osment and said: "You know, this is a really interesting young actor … "

TS: Chris Columbus had made the Home Alone films, so as well as having this global box office ranking as a director, he had a proven ability for working with children.

DH: I suppose Chris Columbus was the most conservative choice from the studio's point of view. But he expressed real passion, and he laid all the groundwork.

NP: We had a director before we had a Harry Potter. It got to the stage where we thought we were never going to find our Harry. Then David found him in the most random of places.

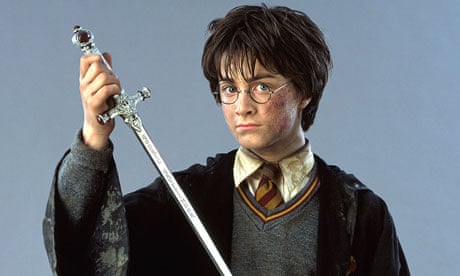

DH: I went to the theatre and I noticed this boy in the audience – he had big eyes, and seemed to be an old soul in a young body. I knew his father, who was with him, so I called the next day to ask if he would bring Dan in to audition. What I didn't know was they'd already turned the request down once – Chris had seen him in the BBC's David Copperfield – but I persuaded Dan and his mother to come for a coffee. This boy was curious and enthusiastic and decent. But it was all about casting the group. We had three or four other boys in the mix, and several Rons and Hermiones.

TS: I watched Emma Watson's screen test and wrote in my notebook: "Perfect! But she is rather beautiful." We did wonder if we should give her a more bucktoothed look, like she has in the book. I remember the first press conference when these three kids were unveiled. They'd been hidden away in a hotel the night before. Rupert was the big surprise, because he was such a natural.

DH: One of the reporters asked Rupert how much he was making. He replied: "I don't know what it is in Muggle money, but I can tell you in Knuts and Galleons."

David Yates, director, HP 5-8: Rupert is the coolest bloke I know. He's so laidback, he's horizontal. But he's a terrible corpser – he always gets the giggles during a take, and that sets everyone else off.

Rupert Grint, actor (Ron Weasley), HP 1-8: Dan said he could set fire to me and I wouldn't react. Actually, that happened once. I was standing too close to a candle and my T-shirt went up in flames. I just started laughing.

TS: We had a commitment to make the first two films back to back, but it was a really tight schedule. We had a November 2001 release date before we had a movie.

DH: Stuart Craig was vital to the films' success, no question. Hogwarts is his creation, his vision.

Stuart Craig, production designer, HP 1-8: I was decorating a bedroom for my as-yet-unborn grandson when I got the call to come to Los Angeles and meet David and Chris. I read the novel on the plane over. My first reaction was fright: How the hell are we going to do this?

TS: We occupied practically the entirety of Leavesden Studios. The top floor was our art department, we had our own zoo, there was a workshop where we built the creatures, as well as seven stages with sets of Hogwarts.

Tim Burke, visual effects supervisor HP 2-6, senior visual effects supervisor HP 7-8: It was this huge family; I think there were over 700 people working at Leavesden, an industry in itself.

SC: When I met Jo, I asked about the geography of Hogwarts. She immediately took out a pen and paper, and made the most extraordinarily complete map on a sheet of A4. I was still referring to that map 10 years later on the eighth film.

TS: Jo never let us know what would happen in the end. We'd send her drafts of each script and she'd say if there was anything that might trip us up down the line.

Matthew Lewis, actor (Neville Longbottom), HP 1-8: It's an odd feeling having your life mapped out, and queuing up at a bookshop to find out what you're going to be doing over the next few years.

SC: The geography and architecture of Hogwarts sometimes didn't fit as we went along because we couldn't have foreseen at the start what was coming. Nobody seemed to mind. Sirius Black was imprisoned in a cell at the top of a tower. A couple of movies later, it was replaced by the astronomy tower from which Dumbledore falls to his death. We took incredible liberties with continuity from one film to another. Everyone has been very tolerant; we seem to be forgiven every time.

TB: Hogwarts was a miniature model originally, and we kept updating the quality of that model all the way up to the final film, where we built it all as a big CG model, including the environment around it.

RG: On my first few days on the first film I felt completely out of my depth.

ML: My first scene was when Neville takes off on the broomstick and crashes around. I was so worried I was going to mess it up, but I ended up really enjoying myself. By the end of the week I thought: "Is this really my job? Bloody hell!"

DH: When the first film opened, no way did I think we'd make eight films. That didn't seem feasible until after we'd done the fourth.

NP: Warners kept a close eye on David, and he made the first film very much the way he felt the studio wanted to make it. Then when they saw he'd done such a fantastic job, they gave him more freedom to make riskier choices with directors.

SC: Chris made the first two films for contemporaries of Harry and his friends. The target audience was 11 or 12, and he aimed it there very skilfully.

TS: By the third film, we were more confident in the fact that the audience and the material was there to stay, so we could be more adventurous. When we knew there would be a vacancy on the third film, we went straight to Alfonso Cuarón.

TB: No disrespect to Chris, but Alfonso definitely upped the ante on Prisoner of Azkaban. He gave the series a more adult feel just when it needed it.

DH: Alfonso really engaged the cast in developing their roles. He asked Dan and Rupert and Emma to each write an essay about their characters. Dan wrote a page, Emma wrote 10 and Rupert didn't deliver anything – they all responded very much in character.

TB: Often people react not to the volume of effects work, but to two or three good characters that carry a film, like the Dementors or the Hippogriff, so maybe that's why we got the Oscar nomination for Prisoner of Azkaban. Alfonso was very interested in effects. He's … yeah, an interesting person. I'm being a bit cagey here. Let's just say he's challenging. High standards, and all sorts of other things.

TS: The fourth film, Goblet of Fire, was a sprawling piece that needed a different approach.

DH: Mike Newell was the first British director to work on the series. He had an innate understanding of British schools, their anarchy, their humour. I was a little concerned when he talked about making it as a Bollywood film, but I see what he meant – it has this big, theatrical feel.

SC: To everyone's delight, Mike made a funny film. It was about dating and teenage angst and who would partner whom at the Yule Ball. Then when David Yates came along, he got the very dramatic stuff, the loss of loved ones and so on.

DH: We asked Chris to do the third film, and he said "No." Same with Alfonso and Mike on the fourth and fifth. They were exhausted. The reason David continued after directing Order of the Phoenix was that he had the energy.

DY: I wanted to grow the films up, make them older, more intense. I don't know where I got the energy to do four of them. I loved the world and didn't want to stop. And having done the fifth and sixth films, I couldn't stand the notion of someone else finishing the series. It's like a rollercoaster: the best place to be is the front or the back; you don't want to be the bloke in the middle.

TB: The final film was the most challenging. We filmed Deathly Hallows Parts 1 and 2 continuously for 18 months, as though it was one big movie.

SC: They weren't even filmed back to back, it was more like interlinked. We'd do bits of Part 2 one day, bits of Part 1 the next.

David Barron, executive producer, HP 2 and 4, producer HP 5-8: The books were getting bigger. When we came to adapt Deathly Hallows, we thought: "Well, the DNA is one book to one film," so we sent Steve away to adapt it. He rang after a few weeks and said: "I can't get this into one movie unless you want it to be four or five hours long." I don't suppose Warner Bros was unhappy about getting two films. Steve even said: "You know what? If you really wanted to push this, you could get three films out of it."

TB: What made Deathly Hallows Part 2 so complicated is that there are so many different areas of battle – Voldemort arrives high up in the mountains, then there's the various sides of Hogwarts, the bridge, the courtyards, the viaduct. It was made even more complicated by having the effects shot in 3D, and the live action converted afterwards. Deathly Hallows Part 1 was supposed to be in 3D, but there wasn't time for the conversion process.

DB: I'm so pleased with the 3D on Deathly Hallows Part 2 – 99% of it goes backwards into the screen rather than forwards into the audience. It pulls you into the film. Voldemort's death scene is particularly beautiful.

ML: On Deathly Hallows Part 2, I had a big scene with Ralph Fiennes. It was the first time I'd met him. He didn't say much before, but throughout the entire reading he didn't take his eyes off me. I was frightened, man! When he did his monologue, it took all my effort just to stop my jaw from dropping. I suddenly had this tunnel vision while we were shooting – it just became me and Ralph. He does that. He fires you up.

RG: With the kissing scene between Ron and Hermione, we felt this pressure to make it look like we wanted to do it, when in reality we didn't. I've known Emma since she was nine; we're like brother and sister. The thought of kissing her just seemed so weird.

TS: One of the great pleasures of the series is to look at the first films, then see how far the younger actors have come; it's like Michael Apted's 7 Up, where you feel you've watched these people grow up on screen, and become part of your family. Every director, and all those great actors, have left their mark on them.

ML: Alan Rickman was brilliant and terrifying. It took me about four or five years just to be able to say to him: "Mornin' Alan." On his last day of shooting I went to his trailer and told him how much working with him had meant to me. He invited me in and we talked about my future. I'm thinking: "Shit! I'm in Alan Rickman's trailer and he's giving me advice on my future!"

RG: Alan sort of stayed in character between takes. I mean, he wasn't evil or anything. But he's quite intimidating.

TB: It's very sad now it's over. You realise that this sort of thing will probably never happen again on this scale.

ML: People were pretty upset on the last day. There was a huge sense of achievement for what we'd done. I never thought, 10 years ago as an 11-year-old boy, that I'd be making eight Harry Potter films.

RG: The week leading up to the last day was weird. I was cleaning out my dressing room, boxing everything up, finding birthday cards from when I was 14. The last day had such a final feeling to it. Ten years had come down to this one shot.

DY: For the very last shot, Dan, Rupert and Emma had to run and jump and throw themselves on to this giant blue mat. I thought that'd be a really appropriate way to end it: a leap into the wide blue yonder. After I yelled "Cut," Dan gave a speech. So did David Heyman and I. It was very emotional.

RG: When David called "Cut," I cried. It was seeing Dan and Emma crying that set me off.

DY: I think Dan has become so assured. He's a workaholic. He loves work, he lives for it. But I worry about him for that reason. He never takes a breath. The day after we finished Harry Potter, he was on his way to New York to start rehearsing for this Broadway show, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.

RG: I had an empty feeling after we finished. I felt a bit lost. I didn't know what to do with myself. But I feel quite liberated now. While we were making the films, we couldn't go skiing or do anything dangerous. And we didn't have complete control over our hair, which sounds ridiculous. Now we can do what we want with our hair. Not that I have, but …

DY: People started on Harry Potter as runners or plasterers and worked their way up. That apprenticeship is gone now; I think that'll leave quite a big hole.

DB: Harry Potter created the UK effects industry as we know it. On the first film, all the complicated visual effects were done on the [US] west coast. But on the second, we took a leap of faith and gave much of what would normally be given to Californian vendors to UK ones. They came up trumps.

TB: Now we're recognised as the leading provider for visual effects in the world. All the studios are bringing their work to UK effects companies. Every facility is fully booked, and that wasn't the case before Harry Potter. That's really significant.

DB: Some people have said the ending of the final film leaves the story open. Personally I think it does the reverse. Despite the extraordinary experiences that Harry, Ron and Hermione have had, they've gone on to have jobs, families, even sending their own kids off to school. Rather than leading to another chapter, I think it's a full stop.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion