"Everything about this program pushes definitions about what is a semester, what is the university, what is a classroom, and where do the faculty belong?"

In the spring of 2008, John Katzman, the founder of the Princeton Review, approached the Masters of Arts in Teaching (MAT) program at at the University of Southern California with a revolutionary idea. USC could increase its graduates by a factor of ten without building another room.

Every year, California adds 10,000 new teachers. And every year until 2008, USC graduated about 100. The school felt "invisible." How could it build influence without new buildings? Katzman said his new project, 2tor, Inc, an education technology company, promised a solution. Forget the brick and mortar, and go online, he said. USC was skeptical. Surely, no Web program could possibly deliver an in-classroom quality of instruction.

"Teachers and students uniformly love it," said Melora Sundt, associate dean of academic programs at USC's Rossier School of Education. "We're bringing people from all over the world into the same classroom." Now in 45 states and 25 countries, including Turkey, Japan and South Korea, USC's online education has gone global.

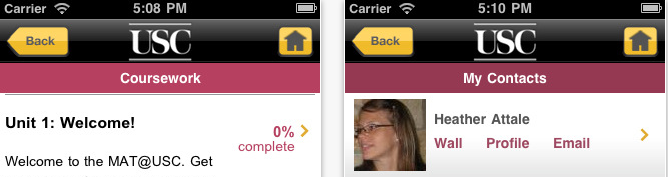

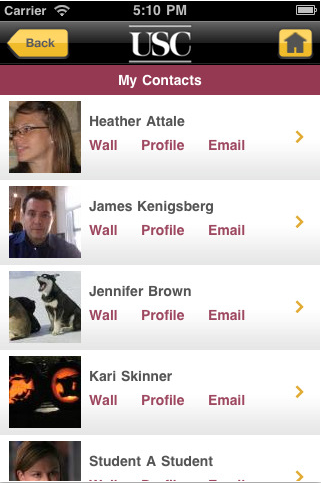

Each student also has an online profile (see left), like a Facebook page, where they can message other students or create online groups (e.g. "MAT in Vegas" or "4th Grade Teachers").

Each student also has an online profile (see left), like a Facebook page, where they can message other students or create online groups (e.g. "MAT in Vegas" or "4th Grade Teachers"). When the program first launched, the school allowed some professors to give a pass to online teaching. One year later, almost the entire faculty become "complete converts." Students called it "life-changing." Professors said it was the most fun they'd had at work in a long time.

"Putting the education online means you can see what issues are universal," Sundt says. "It's wonderful to hear students say, 'I have that issue in Kansas!' and 'I have the same issue in Massachusetts!' Our class becomes the country."

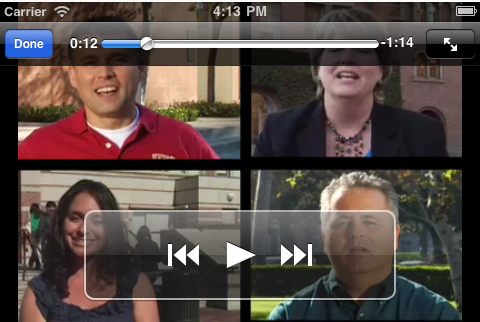

As much as Sundt rhapsodizes about how the program has changed, she's equally emphatic about what hasn't changed at USC. The school still accepts students selectively, still charges the same tuition and still requires 20 weeks of in-classroom practice. Students upload daily videos of their work in classrooms from their home city.

But there's the rub: an online education is only as good as its connection. "Our program is technology dependent, so sometimes things go wrong," she says. "We have alternate sites we can move to. But that's probably the biggest drawback."

In 2009, the same year MAT@USC debuted, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan blasted the teacher education system at Teachers College at Columbia University. "Many, if not most, of the nation's 1,450 schools, colleges and departments of education are doing a mediocre job of preparing teachers for the realities of the 21st-century classroom," he said.

The irony of MAT@USC is that rather than replace teachers with online technology, USC is now creating thousands more. Not only has enrollment at the teacher prep program increased by a factor of ten in three years, but also faculty hiring at the school has kept pace. In 2010, the school had added 25 new full-time faculty plus numerous adjuncts.

Futurists expect technology to dismantle the inefficiencies of a college education, which draws prestige from spending the most money on the most selective group of students. But USC is using technology primarily to expand its resources rather than reduce them. "We taught at a 15-1 ratio, and we still teach at a 15-1 ratio," Sundt says. "We're not mass marketing this to become a course for 3,000. The cost of a USC education hasn't dropped."

The MAT@USC program is still a closed platform. The next step would blast it open. Sundt wants to build an alumni wiki network that could co-write lesson plans and share best practices from around the world. The school is also experimenting with recorded or simulated lessons for topics they can't film as effectively on camera.

If MAT@USC is a revolution, it's a contained revolution. An island nation of innovation. Around the country, the integration of new technology and traditional teaching is happening slowly. Professor by professor, sometimes program by program, but not school by school. Yale has put its lectures online. MIT has built a template for other schools to do the same. But accredited online education at elite schools still hasn't gone viral.

USC's biggest critics are faculties at other universities. They say you have to be in the classroom to learn teaching. USC responds: You do have to be in the classroom, but you don't have to be in Los Angeles.

"Everything about this program pushes definitions about what is a semester, what is the university, what is a classroom, and where do the faculty belong?" Sundt says. "We presented our program to another large research university for their business, law and education school deans. They said they had an online course in committee for two years. Two years! They couldn't believe what we did. Their comment was: 'How did you make this happen?'"

Sundt laughs and says, "This is the future, guys. I kept thinking, this train is going to run right over you."

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.