Over the past week, tens of thousands of people have taken to roaming the streets, interacting with invisible beings that now inhabit our cities.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

These fanatics speak in a special language, undertake hours of devotional activity, and together experience moments of great joy and great sorrow.

It is an obsession, many say, that has taken over their lives, and for which they will sacrifice their bodies. They understand the world in a way the uninitiated cannot.

What sounds like a sudden global religious conversion, is, of course, the launch of Pokémon Go, an augmented reality smartphone game that has restarted the popular culture phenomenon of Pokémon. In many ways, however, Pokémon and religion are not so far apart.

From kami to Caterpie: Pokémon’s mythological origin story

Pokémon owes much of its its conception to creator Satoshi Tajiri’s childhood love of bug collecting, but the mythology and animist religious history of Japan also provided rich inspiration.

Shintoism, Japan’s oldest religion, teaches that the world is inhabited by thousands of kami, or gods. When made offerings of food and incense, kami bestow good luck in business, studies and health, but when disrespected, they can turn vindictive.

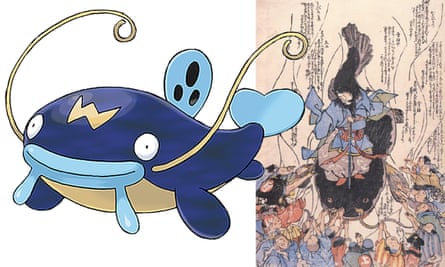

In many cases, the parallels are clear: the water/ground Pokémon Whiscash bears a strong resemblance to namazu, a catfish who causes earthquakes in Japanese mythology; meanwhile, grass/dark Pokémon Shiftry is clearly a tengu or goblin.

Together with the slightly more sinister yōkai (monsters), kami inhabit trees, rivers, rocks and other natural phenomenon, including thunder and lightening. Similarly, Pokémon also live in trees, rivers, rocks and the sky. In Pokémon Go, when offered food and incense, Pokémon become your allies, rewarding players with points and special items. Alternatively, they can run away or resist capture.

In her 2006 book Millennial Monsters, scholar of contemporary Japan Anne Allison argues that popular culture phenomenon such as Pokémon demonstrate a kind of “techno-animism”, which imbues digital technologies with a spirit or soul.

This type of animism is embedded in commodity consumerism, where emotive ties between people and things are used to push products. But it is equally a means of fighting the dislocation of modern life by allowing consumers to create meaning, connection and intimacy in their daily routine.

Two strangers cross in a busy city street, swipe their phones frantically to capture a Bulbasaur, and smile at one other.

Making friends in parking lots just because of Pokèmon GO. Nothing like it

— Justin Denton (@justin_denton10) July 11, 2016

This traditionally spiritual notion – that the material world is alive with beings – has had widespread influence in contemporary Japan. It is apparent in the rampant “cute culture” that labels as kawaii everything from household appliances to aeroplanes. And it surfaces when Marie Kondo asks her readers to thank their shoes and socks for their hard work at the end of each day, in her book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing. This techno-animism also goes some way to explain why robots have been so welcomed into Japanese hearts and homes.

Religion meets technology meets capitalism

We tend to think of religion as diametrically opposed to contemporary technology. In common terms, religion is ancient, transcendent and sacred, invoking the intangible realms of morality and belief, while technology is mechanical, material, modern and profane.

But religions have always relied on the latest technologies to spread the gospel – think the Gutenberg Bible and the invention of the printing press. It’s not surprising then that today, religion has moved online: devotees can download the iRosary application to conduct Catholic prayer on-the-go, listen to podcasts of punk Buddhist dharma, and conduct ancestor worship online.

Modernisation theory, inspired by Max Weber, famously claimed that as societies evolve, religious belief is replaced by scientific rationality. This “disenchantment of the world” was viewed as the inevitable outcome of capitalism. But religion has won, and now resides alongside contemporary capitalism – admittedly, not always comfortably. Pokémon Go is already entangled in a market economy, with pay-to-skip in-app purchases on offer. And as Clem Bastow commented for the Guardian earlier this week, the directive for individual players – “Gotta Catch ‘Em All!” – certainly rings with capitalist zeal.

It will be interesting to see how this relationship develops. Companies and shops that have been designated Pokéstops – where players can earn points and items – are already learning how to lure players towards them; allowing businesses to pay for Pokéstop status (so far predetermined by Niantic labs) seems like the next logical step. How will the devoted Pokémon Go community react to this incursion of profiteering into their sacred space?

The neighbourhood church

As many have said, what’s compelling about Pokémon Go is its immersive play, which blurs reality and fantasy. Using the phone’s GPS and camera functions, it projects a layer of augmented reality onto a mapped streetscape. This allows players to simultaneously inhabit two worlds – one geographic and one imaginary – leading to both humour and danger when they collide.

This article includes content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

Pokémon Go is not the first to do this. Mega Japanese game franchises such as Yōkai Watch and Monster Hunter, both of which draw heavily on Shinto mythology themselves, have similarly launched offline congregations of devotees, who meet in real life cafes and parks to complete online missions in tandem. And location-based mobile games such as BotFighters have been popular since the early 2000s.

The unavoidable comparison here is Ingress, a capture-the-flag augmented-reality game, released by Pokémon Go creator Niantic in 2013, with the backing of Google Maps data. But because Pokémon has nostalgia, a cult following, and cute culture on its side, it promises to transform our offline landscape on a scale never encountered before.

And if the real world has entered the game, then perhaps the opposite is also true. Last week, I saw two Pokémon Go players stopped in the middle of the pathway, staring intently at a real bird.

“I wonder what it’s combat power is?”, one asked.

This article includes content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

Of course, the idea that all or most Japanese genuinely believe their world is inhabited by gods is as ridiculous as the suggestion that all Pokémon Go players do. Not all Shintoists believe kami really exist, and not all Christians believe communion wine and bread are the actual blood and body of Christ. What each groups of devotees have in common, however, is that they act as if these beliefs were true.

I would know: I have spent the last week trouping around the city in a desperate attempt to capture Charmander. So far, the gods have not been in my favour.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion